Playlist

Complete Performance

Translation

| German Text | English Text |

|---|---|

| German Text | English Text |

Analysis

Like BWV 22, this was one of the pair of Cantatas Bach wrote for his audition as Cantor of St. Thomas’ Leipzig in February 1723. It is assumed that one was given before the sermon and one after. Both respond to the same Gospel for the day (the Sunday before Lent). The Gospel tells of Jesus explaining to his disciples that it was time to go to Jerusalem (the subject for BWV 22); and on the way, they pass a blind man who calls out ‘Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me’ -and for his faith, his sight is miraculously restored. It’s that second part of the story which forms the subject matter for Cantata BWV 23.

You can read the text as the blind man saying rather more than he’s quoted as saying in the Gospel! A dramatic imagined exposition of a briefly-told story in Luke, if you like. You can also read it as your own soul’s dialogue with Jesus, pleading that it has faith in him, therefore it claims the rewards of consolation, help and mercy. Both interpretations work equally well.

On the other hand, there’s nothing in either narrative that suggests overwhelming sadness, yet that is what comes through loud and clear in the music. But remember that the disciples’ incomprehension in BWV 22 and the blind man’s entreaty in BWV 23 are both veneers on the underlying story: Jesus is going to Jerusalem, where he will be tortured and crucified, and that’s the background which gives the tone to this piece.

Bach is quite explicit about this, actually. The exquisite opening of the second movement recitative is priceless, largely because the tenor sings his part around a background of very static chord progressions. (The effect is sublime, in my opinion). And if you concentrate on those chords, you will hear the theme of the fourth movement played out. Here are the oboe notes from the second movement:

And here’s the soprano part from the fourth movement:

The note values have halved and there’s been some transposition… but it’s clearly the same theme in both cases. (I should mention in passing that my midi skills are such that I make no attempt to get the tempo right in these music samples…)

And what words are the sopranos singing in that fourth movement to those notes? “Christe, du Lamm Gottes…” -i.e., from the Agnus Dei, ‘Christ, Lamb of God’… and we know what happens to sacrificial lambs. So at the very point where the blind man is talking about not letting Christ pass by without a blessing, the music tells us that Christ’s Easter sacrifice is being prepared for. Hence the sense of melancholy underneath the apparently joyful expressions of recognition and faith.

Is there a more soulful, beautiful bar of music than bar 13 of the second movement, by the way?!

It is sometimes claimed that Bach only wrote a three movement cantata and tacked on the fourth having arrived at Leipzig for the job interview, realising that what he’d prepared wasn’t quite up to the job. How it happens that Bach is quoting the Chorale tune from the fourth movement in the second when he allegedly hadn’t decided to write the fourth at all is a bit of a mystery, then… I’m inclined to think the fourth movement isn’t ‘tacked on’ at all, but was always an integral part of the design.

That ‘Christe, du Lamm Gottes’ theme is riddled throughout the fourth movement, by the way: it’s not just the tune the sopranos sing. They sing B flat -> C -> D -> D -> E flat -> D. Note the tone steps up the scale and the repeated Ds, before stepping downwards a semi-tone.

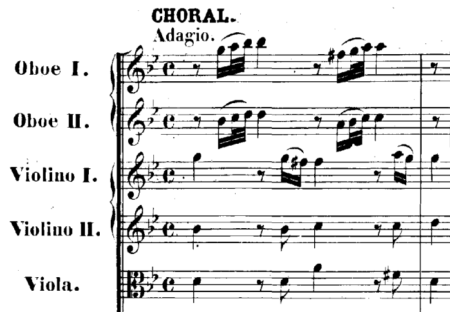

Now look at what the oboes and violins play at its very beginning:

That first oboe takes a tone step from G to A, before repeating the two top B flats and letting the violin kick in with a semi-tone steps down the scale from G to F sharp. It’s not identical, but its suggestive. The same sort of pattern repeats throughout the piece. It’s a sort of leitmotif for ‘impending passion’, because Christ is the paschal lamb of God.

What strikes me about this cantata is that it isn’t a bold, obvious and dramatic flourish, but a carefully worked-through piece of ‘brain music’. It is musically exquisite -and intellectually crafted. It’s not a grab for the emotions, but it nevertheless manages to evoke them through perfectly executed technique. For me, emotions can pall: they get a bit much after a while. Whereas intellectual “games” of the sort Bach is playing here mean there’s endless fascination to be had: some new twist to discover at every hearing.

It is a fine cantata, in other words. I’m glad it got him the job!