Playlist

Translation

| German Text | English Text |

|---|---|

| German Text | English Text |

Analysis

The Visitation is described in the gospel Luke (chapter 1): it is the visit of Mary (pregnant at the time with Jesus) to her cousin, Elizabeth (pregnant at the time with St. John the Baptist). On arriving, Elizabeth's baby leapt in her womb, recognising the presence of Christ. Elizabeth responds by uttering the words of the Hail Mary: "Blessed art thou amongst women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb". Mary responds by exclaiming the Magnificat ("My soul doth magnify the Lord"), one of the core and earliest canticles of the Christian faith. Until 1969, the Feast of the Visitation was celebrated on July 2nd (so that's when Bach would have celebrated it); in that year, it was moved to May 31st.

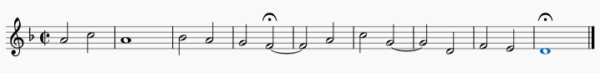

The cantata is, in form, a 'chorale cantata': take a hymn tune, and build variations and harmony upon it to construct the larger work. Unusually, however, there is no hymn tune involved on this occasion! Instead, Bach uses the tune of the ninth psalm-tone, often called the Tonus pergrinus or 'wandering tone', which had been associated since ancient times with the Magnificat. Here's the tune as commonly written out in modern notation:

(Click on the music stave to have the tune played).

Now compare that to the sound of the sopranos as they enter in the first movement chorale:

Hopefully, the family resemblance is obvious. This same theme comes back time and again, throughout the work. Listen to the trumpets during the tenor/alto duet, for example:

The closing chorale is also very obviously grounded on the same 'tune'... and, in fact, it pops up throughout the entire cantata in various forms.

So, the nature of the festival itself and the choice of 'ground tune' tell us from the outset that we're going to hear a paraphrase (by an unknown librettist) of the original Magnificat. Often, the movements' text is taken verbatim from the Magnificat; sometimes, it is in the form of a paraphrase with commentary. Since the Magnificat is a hymn of praise to God, the overall mood of the piece is, inevitably, going to be uplifting, joyous and hopeful. But not if you are rich, mighty or proud, of course, since God will deal with such folk in assorted unpleasant ways -and Bach seems to enjoy depicting the outcome musically in the form of tumbles of semi-quavers into the depths, as we'll see!

The opening chorale is, I think, one of Bach's finest. It's starts with a jolly instrumental sinfonia, with the choir entering after 12 bars. The sopranos, as I've already mentioned carry the cantus firmus tune, supported by doubling trumpets. The lower voices accompany this tune with themes taken from the opening instrumental sinfonia -so everything ties together neatly. When the cantus firmus is repeated, however, Bach switches the tune to be carried by the altos -something he rarely did. Is there any significance to the tune switching from the higher to the lower voice like this? Is it somehow related to 'my soul praises the Lord... I am his lowly hand-maiden'?

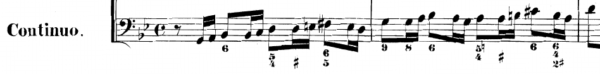

The continuo of this opening movement is distinctive, too, both in score and in sound:

and:

There are clearly large upward movements, followed by long downward movements, through almost two octaves in each direction. Is this, again, a reference to praising things (upwards) and being lowly (downwards)? Or is it a premonition of 'exalting the humble and meek' on the one hand and 'putting down the mighty from their seat' on the other? I am sure some such thoughts were in Bach's mind as he wrote this.

The following soprano aria is another great movement. It opens with a violin flourish that again starts low and works its way up high: this cannot be a coincidence. The lowly is exalted, even amongst violin players! The soprano's (Mary's?) three opening 'Herr' statements similarly start on a lowly B-flat and proceed by thirds to a higher F: I doubt the use of thirds (=trinity) was an accident on Bach's part, either! The busy, scrabbling sound of all the semi-quavers in the continuo and strings suggests excitement and joy (to my ears at least) -and, again, this surely matches the textual mood, of Mary suddenly becoming aware of how highly regarded she, lowly that she is, by God himself. You will notice also that the soprano (as does the oboe) has phrases where she repeats notes several times (for example, when she sings 'Herr, der du stark und mächtig bist, Gott, dessen Name heilig ist' at bars 23-25, with the repeated B flats): if you compare that with the original Tonus peregrius, you will see the family resemblance, I think. It's a movement with a glorious sense of joy and fun about it, in my view, anyway.

The tenor recitative is fairly straightfoward, with things getting musically more interesting at the end ('...seine Hand wie Spreu zerstreum': he will scatter the proud like chaff), as the semi-quaver runs vocally suggest a lot of scattering going on!

The bass aria is a good one! I am tempted to say that you can tell that Bach was looking forward to setting this text, about how the mighty will be thrown from their seats into a lake of brimstone! The busy semi-quaver runs throughout sound like a lot of very mighty people running around in panic. Whether in the accompaniment or in the voice, long stretches of notes are always either rising or falling to the depths -exactly mimicking the text; and the bass gets to enjoy several very low notes, including his last. Lowness is what happens to the mighty when God gets busy, after all!

I've already mentioned the lovely trumpet notes sounding out the cantus firmus once more in the alto/tenor duet that now follows. I should perhaps also mention that Bach was to re-work this duet at a later date to create BWV 648 (one of the Schübler chorales).

The tenor recitative is straightforward narrative -until something strange and rather lovely happens around bar 10: the rocking, interweaving sounds of the strings rocking away strongly suggest ripples on a pond: the text at that point is about Abraham's seed spreading as much as sand on the shore, so a lake-side musical metaphor is, perhaps, appropriate.

The closing chorale is a doxology: praise Father, Son and Holy Ghost, as it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be. The Tonus peregrinus rings out once more in the soprano line; the basses and tenors sing lines that climb ever upwards to make for an interesting harmonisation as we approach the final 'Amen'.

The Gregorian chant that permeates this entire cantata gives the work a nicely 'complex and complete' feel. There are some lovely individual movements (the opening chorus, the soprano and bass arias especially). There is fun word-painting (the bass descending to the depths, for example). I think you can tell Bach enjoyed writing this one -and I find it undoubtedly an A-class cantata to listen to, as well.