Playlist

Complete Performance

Translation

| German Text | English Text |

|---|---|

| German Text | English Text |

Analysis

This Easter Monday cantata was written in 1725 and would have been performed that year on April 2nd. Bach's text (by an anonymous librettist) opens with a quote from St. Luke's gospel concerning the journey of two disciples on the road to Emmaus, during which an unknown man joins them on their walk. The disciples do not recognise him, but as the evening draws on, they ask him to stay with them (uttering the phrase which gives this cantata its title and opening chorus words). As he breaks bread with them, they suddenly realise who he is, the risen Christ, who promptly disappears the moment they recognise him. The librettist draws on the story's setting of approaching evening to provide the metaphor of encroaching darkness (i.e., sin) and Jesus as the light in the darkness (i.e., forgiveness).

Musically, the work is divided up by two chorale movements (movements 3 and 6). The third movement is based on a hymn by Philipp Melanchthon from 1579 (Vespera iam venit) and movement six is based on Luther's 1542 hymn Erhalt uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort. It has been suggested that this arrangement made it possible for part 1 (movements 1-3) to be sung before the day's sermon and part 2 (movements 4-6) after it -but there is precisely zero evidence for this.

The opening chorus is wonderful and sounds as if it should be part of a larger Oratorio or Passion of some sort: perhaps because it sounds strongly like the closing Ruht wohl chorus of Bach's own St. John Passion. The two oboes (plus an oboe da caccia) weave about each other deliciously and rather sensuously, though the overall effect of oboes (to these ears, at least) is generally mournful and sad. The middle section is is in the form of a 4-part fugue and loses the oboes for the most part... and in consequence sounds much brighter and altogether much perkier... but that mood is soon snuffed out and the original gloom descends once more to close the movement.

Cantata second movements are often recitatives, but on this occasion we're treated to a rather fine alto aria with oboe da caccia obbligato. Notice the little rising-note inflection on the opening word 'Hoch...': a little bit of word-painting there from Bach, who clearly thought that 'high-praised' required higher notes! The use of an alto voice comes across as slightly 'darker' than a soprano's would have: which fits in well with the alto's expressed fears for encircling darkness.

The third movement is also known to us as one of the Schübler chorales (BWV 649). The use of a soprano to declaim the theme necessitates the use of a lower-pitched obbligato instrument by way of contrast -and here, we get a piccolo cello. It dances around the soprano as she maintains the unvarying chorale tune in a rather delightful manner. The effect is of the piercing soprano voice emerging, like a beacon, from a sea of darker instrumental music -which, given the words being sung, is another highly appropriate colouring effect for Bach to have conjoured.

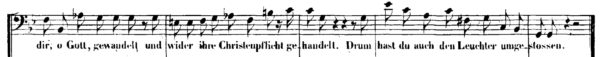

The Bass sings the only recitative in the work: his opening low, dark tones are inevitably tailored to the words, where darkness has apparently won out over the light. His closing statement (about the candles being snuffed out, Drum hast du auch den Leuchter umgestoßen) requires him to sing a line downwards over almost two octaves and end up grubbing around in the vocal basement on low Gs:

It's another effective piece of word-painting!

The tenor aria (movement 5) by contrast entreats the light of Jesus to continue to shine. The flickering violin figures in the accompaniment, together with the more florid parts of the tenor's vocal line, depict the (candle) light most effectively. Dürr claims that the opening notes (on 'Jesu' for the tenor) depict a cross -but you'd have to be more imaginitive than me to see (or hear!) it.

The final chorale is short and ends on a chord of G minor: which is a 'dark' key, sounding rather more mournful than an equivalent major chord would have sounded. It perhaps suggests some uncertainty about the outcome of the Light v. Darkness struggle, despite the confident-sounding words being sung -which is, perhaps, a more realistic outcome for our imperfect world than a joyous chorus of triumph would have brought to mind!

There are some very nice touches in this piece: the opening chorus for one, plus the soprano aria for a second. It isn't a jolly piece, however. It describes approaching evening (of the soul and of the clock) and sounds accordingly gloomy with few moments of reprieve. It is a serious piece, then: meditative and introspective.