As this website is all about listening to “classical music”, I thought I’d better start off by defining what exactly is meant by the phrase, ‘classical music’, at least when this website uses it!

As this website is all about listening to “classical music”, I thought I’d better start off by defining what exactly is meant by the phrase, ‘classical music’, at least when this website uses it!

At its broadest, the term ‘classical music’ means something that sounds like this:

…or potentially like this:

The first of those samples was written around 925; the second in around 1979. There’s getting on for 1000 years of history between the two …yet both are usually thought to be examples of ‘classical music’ (and both might be played on BBC Radio 3, which might thought to be another defining characteristic of all 'classical music'!)

But using the one term to cover both pieces (and everything in between, written over a thousand years or so) is, I think, stretching language beyond the point where it remains meaningful.

It doesn’t help, either, that there is a period within that thousand-year history when genuinely “Classical” music (with a capital C!) was being written, by the likes of Mozart and Haydn. The truly Classical period, in art, architecture and music, was the few decades around the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century, sandwiched between the Baroque and the Romantic periods.

So, we are cursed with using the term ‘classical music’ when we want to refer to any piece of music that could have been written any time in the last thousand years -or maybe within just the 40-odd years either side of the turn of the 19th century. It’s not really a very helpful term, then, is it?!

It is because of the manifest absurdity of using one term to mean pretty much anything musical written in the past thousand years that other terms are sometimes used in its place, such as ‘Art music’ or ‘Serious music’… but those have their own problems: is a 19th century comic opera ‘serious music’, for starters?! And isn’t Jazz just as much a legitimate art form as a violin concerto by Mozart?

But let me take one word from that last paragraph as the real key to what we’re talking about here: “written”. That which we call ‘classical music’ is all, for the most part, written down, on a stave (or staff), indicating pitch, note durations and rhythm. Classical music is a literate form of music -in a way that, for example, ‘pop’ music rarely is. Compare Beethoven’s ability to write down the music of his 9th Symphony when completely deaf -the same notes we play today in much the same way as Beethoven intended with his ‘inner ear’- to the way the Beatles ‘wrote’ their music, for example:

In their early years, Lennon and McCartney wrote songs together and one of their rules was that if they wrote a song but then couldn’t remember how it went, they’d junk it. Since they were trying to write songs that were catchy, this rule worked very well. They wrote words down and changed them on the page, and they might scribble guitar chord names above the words, but as far as the tunes and guitar parts were concerned, they just remembered them.

Later, when their songs were going to be published, they were transcribed by other people. George Martin was writing down the melody of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’, which is in G, and in the line ‘And I’ve been working like a dog’, he couldn’t figure out what note Lennon was singing; I would characterise it as an untempered F. Martin asked Lennon if it was E or F, and Lennon replied ‘Yeah, one of those.’ He went with F.

(Source: https://bit.ly/2pIfGyn)

This can be generalised:

What most [pop music] bands do will [be to] write down the stanza chords and parenthesize the chorus chords. They will remember the harmony, so the music ends up like A-C-G (Em-G). The hard part falls onto the lead guitarist, who has to memorize the note structures. This is why so many intermediate groups rarely play the same leads on their original songs. Without notation, a lead guitarist may need a photographic memory to play it exactly each time.

(Source: https://bit.ly/2pIfGyn)

Putting it bluntly, though without put-down or implied contempt, popular music is composed ‘by ear’ and notated crudely (if at all) with, perhaps, some basic guitar chord tablatures. What we call classical music probably also began life as something composed by ear and shared with others by informal repetition and memorisation -but as the Roman Catholic church wanted to standardise its liturgical performances across the European continent, from around the 9th century onwards, they began to write their ‘tunes’ down, providing a ‘musical text’ which could be shared and learned from.

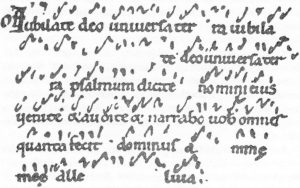

Very early liturgical chants were notated in pitch-less fashion:

The squiggles above and below the words indicate relative note duration and whether the intonation goes up or down, but doesn’t indicate an absolute pitch to start (or finish) on.

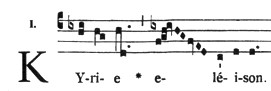

But by the 1200s, the liturgy was being notated in a way that looks much more familiar to modern musical eyes:

Here, we have note duration and pitch up-and-down-ness as before -but we also have a proper stave whose very first character indicates a starting pitch -at which point, we now have absolute and relative pitches plus note duration and rhythm notated very much as we would do it today.

The notation (and the ‘rules’ governing its use) develops, of course, over the ensuing centuries, so that Beethoven scores look like this:

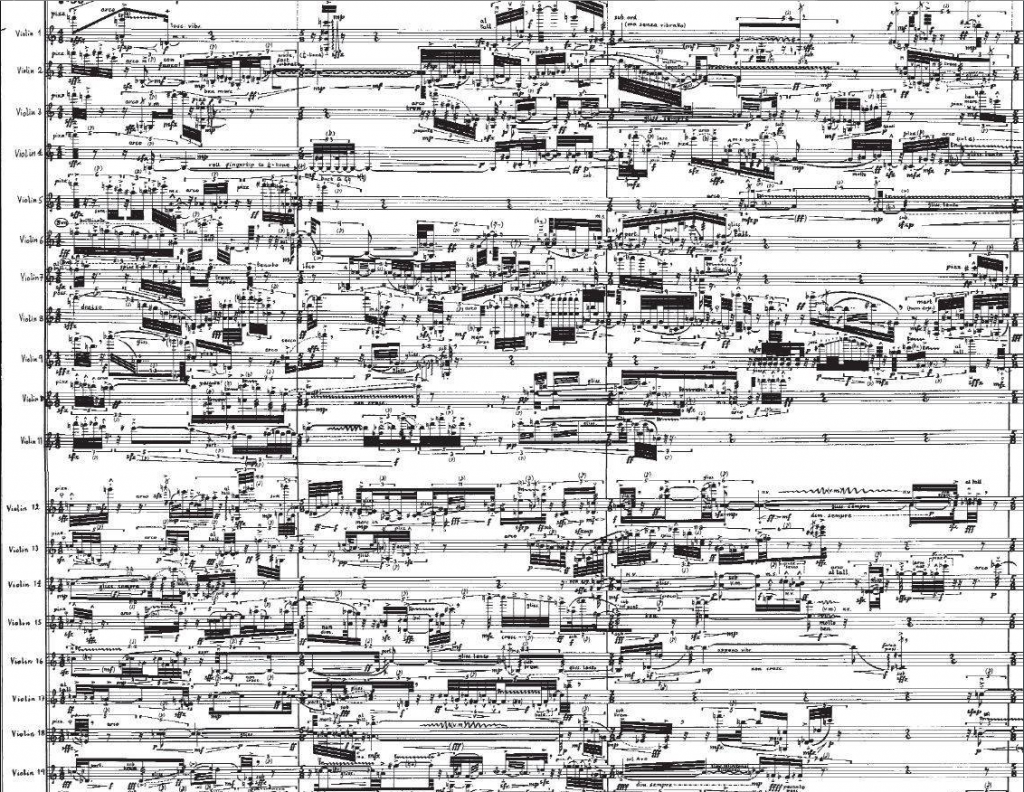

And Brian Ferneyhough scores can look like this:

…which seems terrifying to my eyes (and my ears are none too pleased with the results, either!)

Accompanying the technical progression in the way the music was written, so the music textures being used developed from simple monophony (everyone in a choir singing the same single-line tune at the same time), through polyphony (multiple independent lines sung or performed at once in a way that harmonised nicely) and on to heterophony (multiple independent tunes performed simultaneously without regard for how the independent lines would sound together at any given point).

What began as strictly for the choir to sing in a church similarly developed into secular music to be performed in the privacy of your own home (‘chamber music’) or huge works to be performed in a large concert hall by a cast of thousands (‘orchestral’ or ‘symphonic’ music). You were originally to be elevated into the presence of God by it, but you could soon dance your heart out to it (or do both at once in the case of Johann Sebastian Bach!) Operas could tell a story in song, or a ballet in movement.

So, whatever its precise form or function, this website is about that body of music which was written down by assorted musicians and composers in the mainstream European tradition (which means some Russian, Japanese, Australian and USA composers count, too!), sometime between about 1000AD and 2019AD, for whatever purpose they had in mind at the time. Calling it ‘classical music’ is probably silly, as the term is way too broad and lacking in specific meaning -but that’s what this site means by it, at least.

Speaking entirely personally, classical music -as just defined- is the ‘very ground of my being’, the one thing that helps me make sense of life and my place in it. I’m not a professional musician or musicologist -just someone who finds music intellectually and emotionally stimulating and satisfying. I have sung in several Cathedral and Church choirs; I can read music very fluently (but write it badly); I can bash a tune out on the piano but cannot be said to be actually able to play it. I am, therefore, strictly a barely capable amateur! I should very much have liked my life to have been more deeply involved with professional music-making than it has turned out to be - and I would imagine that my love of music is, at least in part, vicarious accordingly. But my enthusiasm is no less real for that and I hope to be able to convey the reasons for some of it in these pages!