1.0 Introduction

1.0 Introduction

How one goes about organising a large collection of digital classical music is a problem that has many potential solutions. Here, I offer you some guidelines as to how I think you might go about creating a well-organised, easily-searched, efficient and effective classical music library.

This article takes as its starting point the idea of a natural 'primary key to classical music recordings', as previously discussed in this article. You should read that article if you haven't already done so, because it explains what the fundamental pieces of metadata are with which we need to tag our digital music files. Once you understand that principle, quite a lot of everything else falls naturally and fairly easily into place.

I have called the 'points' I bring up "axioms": self-evident truths requiring no proof. Partly this is tongue-in-cheek: they probably do require proofs but I have neither the time nor patience to provide it! But partly it's not quite so tongue-in-cheek: I've been using these principles, refined over time, for more than 2 decades to do my own music tagging -and I think, therefore, that the principles that have worked for me are likely to work for you too. If the word 'axiom' bugs you, however, with its hint of exalted arrogance, feel free to substitute in words like 'principle', 'rule', 'proposal' or whatever else seems more fit!

Axiom 1: The Tags we need (and the ones we don't!)

FLAC files (the sort I think you should store your digital music in) use Vorbis Comments to store metadata about the music contained in the FLAC file in a practically unlimited set of key=value pairs (technically, there can only be 4 billion such pairs per file, but that's practically unlimited). You declare the nature of the data by giving the key a name; you then assign some meaning to the data by assigning a value for that key. For example, "artist=britten" or "album=symphony no. 5".

Since there is no practical limit to the number of these key/value pairs you can create, you could cook up such delights as "recording_engineer=John Culshaw" or "Key_Signature=E flat major". Or even "Tea_Lady=Mrs. Hudson".

Such key/value pairs would technically be described as "custom tags". More bluntly (and more accurately), they should be described as "bonkers".

The trouble with custom tags is that hardly any music playing software displays them or uses them for searching and ordering your music. Want to find all the music you own that's in the key of E flat major? Well, good luck trying to search that Key_Signature tag you created to store that sort of information: no player I can think of will let you do it by default. Few will even display that information in a column when found. Which might mean it's time to invest in new playing software -or it might mean that the world in general has decided that this sort of information isn't really useful to see or find when it comes to the common business of playing music.

Bear in mind, too, that your music files are not the only source of information in the world. You don't need to tag then with the kitchen sink of data, because you can always visit Wikipedia, Google, IMSLP or any number of other websites to find this sort of fairly esoteric data.

So, the point of Axiom 1 in this list is that there is a hard core of tags you ought to tag your music files with and a wild bunch of data which you could tag them with but shouldn't.

And here is my asserted list of must-have tags:

- COMPOSER

- ARTIST

- PERFORMER

- ALBUM

- GENRE

- COMMENT

- TRACKNUMBER

- TITLE

And here is a list of tags you will commonly see advocated for use, but which you should never use:

- ALBUM ARTIST

- LYRICS

- CONDUCTOR

- BAND or ORCHESTRA

- KEY

Plus all the other crazy tags (like recording engineer!) that are really of no use to anyone except the kind of classical music listener that probably does train spotting. I don't collect details such as recording engineer or record label because those are, I think, not relevant to the business of choosing, finding and playing classical music. If you are someone that thinks, 'If it's on Decca, the recording quality is probably good, but if it's DG, then it might be ropey' and that sort of thing affects your choice of music, then be my guest and create custom tags for that sort of data... but good luck finding a player that will ever let you use or display that data.

Putting this from the other direction: Axiom 1 states that there are only 8 pieces of information you need to record about any piece of classical music. Everything else is a waste of time.

Axiom 2: ARTIST and COMPOSER are the same thing

People tend to get quite defensive about this, but whether a recording is conducted by Karajan or Boult or Rattle is much less significant than whether the guy who wrote the music being recorded was called Beethoven or Bruckner. The performers of the work are useful to know for finding a recording to play -so you certainly need to be able to search and discover music conducted by X, or played by Y. But the organising principle of your classical music collection must be by the composers who created its contents in the first place.

Ideally, we would therefore tag our music with the COMPOSER tag, and that would get our music collection organised nicely. Unfortunately, hardly any music player written offers to sort and group your music by the COMPOSER tag, if they are even aware it exists -so putting all your tagging eggs into the COMPOSER basket would be pointless. Nearly all music players tend to organise, sort and group their music by ARTIST, however.

So, ideally, we would tag and organise by COMPOSER; practically we need to tag and organise by ARTIST. The logical solution to this apparent dilemma is therefore quite straightforward: COMPOSER and ARTIST tags must be filled with the same data, always.

Now, technically, in data theory, we don't like data found in one place being duplicated in a second -because that means you've got two bits of independent data which ought to be the same, but there's no mechanism available to make them be the same. They could therefore drift apart and end up with different values, and then you've no basis for saying which of the values (if either) is the correct one. So data purists would say, 'Since players only use the ARTIST tag, only fill in the ARTIST tag, and forget all about the COMPOSER tag entirely'.

They would not be wrong: that is the technically correct approach to take.

But I have found over the years that classical music listeners really don't like not having a tag called 'COMPOSER'. It is a central feature of classical music, after all! So, whilst Axiom 2 states that ARTIST must always be the same as COMPOSER, a rider to that axiom is 'unless you choose not to fill in the COMPOSER tag at all'.

Axiom 3: COMMENT is where performer details go

If ARTIST is going to be used to store the composer's name, where do you stick the details of, er, the artists making the recording? Well, PERFORMER seems plausible -but it often is not exposed by many media players, and is rarely searchable. So sticking the details there doesn't really 'expose' that data in a useful way. You will, after all, want to be able to find music that's being performed by the Berlin Philharmonic or conducted by Simon Rattle... that data needs to be searchable.

The one tag which is commonly displayed and made searchable in every media player with which I'm familiar is COMMENT. Therefore, Axiom 3 states that performer details are always stored in COMMENTS.

A rider to this axiom is that 'and they should be entered in a consistent manner and in a consistent, coherent order'. I would suggest, for example, that you always enter performer details in the order: conductor, orchestra, choir, soloists. And another rider to the axiom is that you spell out the function of each soloists, in brackets -so that you have, for example, "Fred Dimples (baritone)" or "Freda Wimples (harp)". It, of course, goes without saying (though I'm about to say it!) that if there is no choir on a recording, or no soloists taking part in this performance of a symphony... you simply miss out the components that don't apply.

There's no particular reason for that suggested ordering, by the way, except that it mirrors what I think most people's sense of 'order of precedence' regarding classical music recordings. "Oh, Karajan's fifth is great" or "Solti's Ring is the best"... such statements tend to indicate that we think of the conductor as being of more 'weight' than whoever the orchestra or soloists might be. You'll then hear critics talking about 'Karajan's recording of that symphony with the Vienna Phil were much better than when he tried it with the Czech Symphony Orchestra' -and that again suggests that after conductors, we think primarily about the major orchestra involved. And so on.

The key thing, however, is not so much a specific ordering as that you are always consistent about whatever ordering you decide on. It would be handy to be able to say 'the first name in the list, before the first comma, is always the conductor's', for example. You'll find you can manipulate and manage your data much better later on if it has been entered in a consistent -and thus predictable- format.

Axiom 4: GENRE is a single word sub-division, not a musicological exactitude

Every piece of music you own should be assigned a 'genre' -an adjective (usually!) which describes the general 'type' of music we're talking about. It's purpose is to divide a composer's music up into manageable sub-sections, rather than see everything a composer wrote in one enormous and un-navigable list.

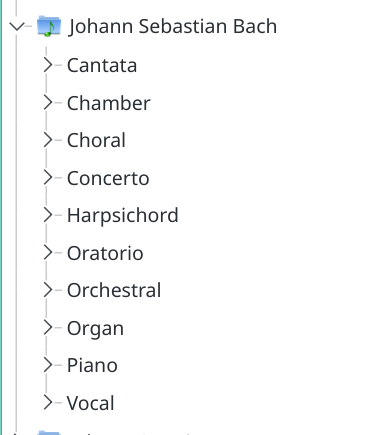

When I dive into my collection of Johann Sebastian Bach, for example, I want to see this:

...and not this:

In the first case, if I want to listen to Cantata 140, I know roughly where to start looking. In the second case, I haven't got a clue -and even if I remember it's first line starts 'Wachet Auf!', I really don't want to have to scroll through all works named A to V before I can find it!

GENRE provides a logical grouping of works, keeping a composer's choral pieces in separate 'virtual locations' in your music library away from his symphonies or chamber works.

GENRE should not, however, be allowed to become a demonstration of musicological nit-picking. Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 is a symphony, not a choral work, or an orchestral work-with-choral end piece, or 'Symphony/Orchestral/Choral', for example. For similar reasons, we'd group operas together without trying to be academically clever about tagging them as 'opera seria' versus 'opera buffa', for example. For the same sorts of reasons, grouping things as 'chamber' is fine, but grouping them as 'string quartets', 'string quintets', 'sextets', 'octets', 'nonets' and so on and on would be silly: the more precise and 'accurate' your genres, the less useful they are in dividing-and-yet-usefully-grouping a composer's output into usable chunks.

In summary, then, GENRE should always be a one-word summary of the type of work a composition is, not a multi-word, set of nested sub-genres. It should be as precise as needed to break a composer's output up into conveniently-sized chunks, but not so precise that it fractures a composer's ouvre into a bazillion tiny pieces! I've prepared elsewhere a list of what I would consider 'appropriate' genres to use.

So, Axiom 4 states that a single-word, generic but descriptive term for sub-groups of a composer's output should go in the GENRE tag -and with the rider that you shouldn't try to get too precise or picky about what genres you use. I will also acknowledge that I break my own Axiom 4 when I use the genre 'Film - Theatre - Radio' ...but only because I lacked the imagination to come up with a one-word description of the sort of category film scores, music for radio plays and incidental music to theatre productions should use! You'll note that I hyphen-separate the three 'elements' of that genre: there are no forward- or backward-slashes, and I'm not trying to imply a hierarchy or 'compound genre' as is true of the 'Symphony/Orchestral/Choral' example mentioned earlier. I personally don't distinguish between 'Choral - Sacred' and 'Choral - Secular', but if I did, they'd be permitted exemptions to the 'single-word' rule, because they again are merely finding it difficult to describe a genre with one word, not trying to construct a 'compound' or 'multi-level' genre.

Axiom 5: The ALBUM is for the extended Composition Name

You'll have to read my other article on the Primary Keys for Recorded Music to understand why there's such a thing as an 'extended composition name' and what it is precisely, but the short version is: the extended composition name is a combionation of the actual composition name, plus the conductor's (or other distinguishing artist's) surname, plus the recording year. These three pieces of data are all needed because only that combination of information truly, uniquely and invariably identifies one recording of (say) a particular symphony from another. When combined, we refer to these three pieces of information as 'the extended composition name' -and Axiom 5 states that it is the extended composition name which goes into the ALBUM tag.

Consistency of approach is vital here, and I would strongly recommend you to adopt this formatting approach:

Traditional Composition Name (surname - recording year)

...and I mean by this that, literally, you put the distinguishing artist's name and recording year inside brackets with a space-hyphen-space separator, and all of it comes after the 'traditional' name of the composition. You would, for example, end up with something like:

Symphony No. 5 (Karajan - 1966)

My personal preference is not to clutter the 'traditional name' component of this construct with technical detail about opus numbers, catalogue IDs, key signatures, nicknames or anything else which isn't directly the formal composition name. That is, I would not say 'Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67' or 'Symphony No. 101 "Clock" H.1/101', but simply 'Symphony No. 5' or 'Symphony No. 101'. I prefer my 'traditional name' components to be precise and short (because you will play music on devices that don't always have very wide screens and which cannot therefore display long titles in full. Bolting on the distinguishing artist's surname and the recording year already makes album names quite long: I don't like to add to the length if it's not strictly needed. Remember that you can always look information up in Wikipedia or elsewhere: the album name shouldn't be shoved full of information in the apparent belief that it's your only source of information about the work!

There are some exceptions to that last paragraph, however. I find Mozart and Bach in particular have enormous catalogues of music that are quite hard to navigate through and find any particular piece of music within, simply because they wrote so much of it! For those composers alone, therefore, I try to prefix their 'traditional names' with their catalogue numbers.

Hence all my Bach would be tagged as (say) BWV 140 Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme (Suzuki - 2011) or BWV 988 Goldberg Variations (Perahia - 2000). This only works when the catalogue number prefix would usefully group like-minded works together, however, which will happen if the catalogue in question is a thematic one, rather than a chronological one. The Koechel catalogue for Mozart is, unfortunately, vaguely and inaccurately chronological, so rather than prefix all my Mozart with those catalogue numbers, I invented my own thematic catalogue. This has the effect of grouping all symphonies together, all chamber works together, all operas together and so on. In effect, the album name takes on the function of the GENRE tag... and it's not particularly good practice to let one piece of data duplicate the function of another like that. But I find it necessary for Bach and Mozart because of the sheer quantity of music involved. You may feel differently, and that's fine: Axiom 5 does not mandate this approach at all.

Axiom 6: The PERFORMER tag is for the 'distinguishing artist'

For some people, the ability to search for all music recorded by Herbert von Karajan is important. Now, if his name is in the COMMENT tag (as it should be), it will be searchable and discoverable from there... so in that case, there's no real reason to store it anywhere else. Except... it is not always so easy to search within a large chunk of text for a specific substring. I mean, you might tag the COMMENT as Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic: how certain are you that your music player will see "Karajan" and "," as separate things? Some will, some might not. It's really the uncertainty that's the issue here: and the way to fix it is to repeat the conductor (or other 'distinguishing' name) in the PERFORMER tag, freed from all encumbrances of surrounding text or punctuation. It means you should be able to search the PERFORMER tag for "Karajan" and be certain of finding a match, because you won't be dealing with "Karajan," entries that might or might not match.

Repeating data in more than one place is not ideal, for reasons already discussed (see Axiom 2), and I was a late convert to the need for anything in the PERFORMER tag at all. The main problem is that its use really sets up an unspoken 'rule' that the first entry in the COMMENT tag matches what is in the PERFORMER tag... but there's no mechanism that can enforce that rule, so it's perfectly possible that having started out matching, the two bits of data could diverge over time... and then you have no real idea of which is the right value, assuming either of them is 'right' in the first place.

Axiom 6 is a breach of normal data modelling rules, but I think its usefulness to search and music discovery processes outweighs the theoretical objections on this occasion. Axiom 6 therefore states that the distinguishing artist's full name will appear in the PERFORMER tag.

Axiom 7: The YEAR tag is for (an approximation of) the Recording Year

A little like Axiom 6, we repeat another piece of data when it comes to the Recording Year. It's already in the extended composition name and thus in the ALBUM tag (see Axiom 5). We now repeat that same year in a dedicated YEAR tag.

Technically, it's data repetition and that's a bad thing: but unfortunately a lot of music players think that sorting things by their recording year is a sensible thing to do (it isn't for classical music!), so it's better to have some data in the relevant tag than to simply leave it blank and give no clue whatever to such players.

The YEAR should only be a year: do not ever be tempted to put in specific day-month-year type of dates: there's no point, and Americans will put numbers in the wrong way round as far as Europeans are concerned anyway! Quite often, it's hard to find out even a specific recording year, so it's rather pointless to pretend that you can get a highly day- or month-specific use out of the field.

Fundamentally, too, the YEAR is of little use to anyone except in specific circumstances. When we're talking about Megastar Conductors re-re-recording the symphonies of equally Megastar Composers, then fine: being able to distinguish between Karajan's 1960 cycle and his 1970s one is important, just as it's useful to be able to tell Boult's 1958 recording of Vaughan Williams' 9th Symphony from his 1969 one. But these sorts of exceptions aside, no-one really cares whether Rattle conducted Szymanowski's 3rd symphony in 1992 or 1993, so being fanatically precise about it, for nearly any normal listener of music, is pointless pedantry.

When in doubt, see if you can find a ℗ date in the recording's booklet: the recording date will probably be the year before that, or -sometimes- the year before that. So if you see ℗ 1976, the recording year might be entered as 1974 or 1975 (it's more likely than not that 1975 would be the 'correct' year, but it is not invariably so).

Anyway, Axiom 7 states that the YEAR tag is to store the approximate or known year of recording, not a specific date.

Axiom 8: The only track-specific metadata are track number and title

Axiom 8 is a little by way of summing up: everything discussed up to this point has been information that is of 'extended composition-wide' significance. The conductor, the orchestra, the soloists, the recording year, the composition name, the principle artist: all these things are pieces of data which apply to the entire composition, without exception.

The corollary to this observation is that things like performing artists names, soloists and so on do not change on a per-track basis. I realise that in an opera recording, you'll have a Maria Callas aria in track 16 and a Giuseppe di Stefano aria by way of rebuttal in track 17. But we do not tag each track with whoever happens to be singing on that track.

There are two basic reasons for this: first, it would take you an age and a half to mark up a CD rip if you had to keep chopping and changing the contents of the COMMENT tag on a per-track basis. The harpsichordist is silent in tracks 4, 5, and 8, but needs mentioning in tracks 1,2,3 and 7?? Forget it! Just say there's a harpsichordist playing throughout the entire composition. And here's reason number two: because you've got a pair of ears that can work out whether it's a soprano singing here and a tenor there; or a harpsichordist there and an oboist here.

So, COMPOSER, ARTIST, ALBUM, COMMENT, PERFORMER, YEAR, GENRE are all composition-wide tags. That means, as Axiom 8 states, that only TRACKNUMBER and TITLE are track-specific pieces of information.

Another implication of this axiom is quite profound: since ALBUM is composition-wide, if you've got a single CD with Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 and Mozart's Symphony No. 40 on it, the 8 tracks of that CD cannot share the same ALBUM tag. Therefore, they have to be ripped as two separate compositions, each of which can have their own, unique ALBUM tag. It is, in other words, never acceptable to rip a CD as a single 'entity' called 'Classic Symphonies' with track 1 labelled 'Beethoven: Symphony No. 5: Allegro con brio' and track 5 labelled 'Mozart: Symphony No. 40: Molto allegro'. This would make 'composer' something that is track-specific, and that breaks Axiom 8.

Axiom 9: TRACKNUMBER always starts at 1

When you rip a multi-work CD, as just described in discussing Axiom 8, you will end up with separate works ripped into separate physical folders (because only that way can the same ALBUM tag be applied to each without being inaccurate in any case). That means you'll be ripping (say) tracks 1 to 4 into the Beethoven Symphony No. 5 folder and tracks 5 to 8 into the Mozart Symphony No. 40 folder.

Axiom 9 states that TRACKNUMBER must always start at 1, no matter what the track number on the original CD may have been.

In other words, just as Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 has a Track 1 - Allegro con brio, so Mozart's Symphony No. 40 must have a Track 1 - Molto allegro.

Practically and functionally, the four movements of Mozart's symphony could be numbered 73 to 76 and no-one would particularly notice or mind! Music players will play what they're told to play, and so long as the track numbers increment appropriately, all four movements will get played in order regardless.

But philosophically, I insist on 'every composition starts at track 1' because it's important to break the nexus people seem to assume exists between compositions and the pieces of plastic they are shipped to us on. That Beethoven's 5th and Mozart's 40th share a piece of physical, silvered polycarbonate and a printed booklet is as relevant as the fact that my birthday card came in a brown envelope. It's the card that counts, not the envelope! In the same way, the physical CD is merely an envelope, and it's the fact that you own Beethoven's 5th and Mozart's 40th -two entirely separate compositions- that your music library should celebrate and be organised around.

Thus, each composition is unique and separate ...and deserves to have its first movement start at number 1.

Axiom 10: TITLE should be musically factual, not full of extraneous detail

When it comes to track titles, people often seem to lose their heads. I've seen this sort of thing:

Act III, Scene 1: Addio mio (Elvira, aria with chorus, in front of the temple)

So, first thing to say, we're merely listeners of music, not theatrical impresarios: we don't need stage directions, characters names, mis-en-scène or any of the other nonsense you see in this (made-up) example. To know whereabouts you are in an opera (which Act, which scene), follow the libretto and work it out from there: your music player probably doesn't have the screen width to tell you properly anyway (most of the above will get truncated if you try playing it on your phone, for example!). If you are wondering whether Elvira is stabbing someone or praying before the temple -read the libretto and learn the damn opera! Don't use your music player as a prop for things you should be studying, learning about and remembering from elsewhere!

The correct tag for this track is actually Addio mio... and the only reason, really, we need this much information is just as a minor checkpoint on the way through the entire work, we can match up what we see in the TITLE tag with what we hear and know where we are within the 76 tracks that make up this opera. We use TITLE as 'touch points', little re-assurances to let us know approximately how far we've come and how far we still have to go. They are not designed to be encyclopædic entries of exactitude, letting you stage-direct the thing in your head! Nor are they supposed to contain every tempo nuance that might take place within a symphony's movement. Read the score for that sort of detail!

In general, and in principle, the TITLE tag should be the first line of the words being sung at that point, or the tempo marking associated with that movement, or whatever other musical fact it makes sense to draw attention to.

So, no full-on lyrics. No full-on tempi changes listed to the nᵗʰ degree. Keep it simple, stick to musical facts (or, when words are involved, simple lexical facts) -and keep them basic and highly functional. Let your ears tell you if it's Elvira or Don Juan singing, a chorus or an orchestra interlude. Use a score to find out more detail about whether it's Allegro at bar 67 or Adagio at bar 134: your music collection/database is not the only source of information on the planet, so you don't have to cram everything into it, just in case!

There are obviously exceptions to this. I personally always tag the first track of a new Act with the relevant Act number. So, you'd see this sort of thing:

Track 01 : Act 1: Overture Track 02 : Oh caro, la gamba della mia signora è fasciata Track 03 : Devo preparare un bagel Track 04 : Ma che diavolo è questo pan di zenzero? Track 05 : Act 2: Entr'acte ...

...so that you periodically get a check of where you are in the big scheme of things, but you don't bog down every track with extraneous dramaturgical detail.

It's also the case that, in obeying Axiom 5, I may well have omitted some technical details. The TITLE is a place where I might put them back. For example, if I've tagged something as merely "Symphony 13", I might tag the first track's TITLE with 'Symphony No. 13, Op. 61: Allegro", so that the opus number finally makes an appearance somewhere in the metadata.

Quite often, though, the title won't be much more than a repetition of the ALBUM tag, in works that consist of only a single movement: ALBUM=Adagio, Op. 72 (Karajan - 1972), TITLE=Adagio. That's fine when it happens: just accept that in single-movement works, there's not a lot the TITLE can say that the ALBUM hasn't already. It's duplicative, but it's also the nature of the beast, so there's not a lot to do about it.

Summary So Far

For my American friends, I think I should now summarise the first 10 articles of the Bill of Rights Axioms so that we're clear about everything up to this point:

Axiom 1: There are 8 tags you must have; all the rest are optional or downright not wanted

Axiom 2: Artist=Composer

Axiom 3: Comment=List of all performers, in a specified and consistent comma-separated order

Axiom 4: Genre=A one-word subdivision of a composer's works into usable chunks

Axiom 5: Album = Composition Name (Artist - Year)

Axiom 6: Performer = Distinguishing Artist's full name, with no punctuation or elaboration

Axiom 7: Year=Approximate (or known) year of recording, in four digit format, no specific dates

Axiom 8: Axioms 1 to 7 apply composition-wide; only 9 & 10 are track-specific

Axiom 9: Every composition should start with a track number 1

Axiom 10: Track titles are for abbreviated music facts, not dramatic details or musicological tours de force!

Having got those out of the way, I now want to specify a handful of more 'nuanced' Axioms -meaning that I think they are self-evidently true, but they are fundamentally a matter of taste and your taste might not be mine! But I want to emphasise that my 'taste' has been refined from over two decades of having to live with the results of my tagging handiwork, so I think there might be a 'compelling truth' to them, too 🙂

Axiom 11: There is no place for a Disc Number

Some CD rippers offer to put a 'disk number' tag in, or a 'CD number'. Axiom 11 states that your music files should never contain a disc number or anything equivalent.

Disc numbers only make sense in a world in which you've got (for example) Götterdämmerung Disc 1, Disc 2, Disc 3 and Disc 4. And that only makes sense in a world of physical CD media. In the world of digital media, you'd rip all four disks, label them sequentially from track 1 to track 54, and call the whole set 'Götterdämmerung'. Which is to say, there are no discs in digital music and it's therefore silly to tag your tracks up as coming from particular pieces of physical media that, the moment you've ripped them, you know nothing about and care less.

Never supply a disc number or anything that resembles it: that way, attachment to physical media lies (and see Axiom 9 whilst you're at it: you need to break this nexus between physical media and the music you listen to!)

Axiom 12: Composers were people with more than just surnames!

If you ever listen in to classical music fans talking about their favourites, you may just think you've been transported back in time to an Edwardian public school. Though instead of 'Smythe did well this year at cricket' and "Oddknob is doing well at Latin, but Grimshaw got sent down early for spiking the Governors' Day punch", you'll hear things like 'Mozart's 40th is wonderful' or 'I can't be doing with Bruckner's 6th'.

Composers were (shocking fact, I realise) people... and they had names. Full and wonderful names that (usually) consisted of at least one Christian name and a surname... and referring to them only by their surnames is, in my view, rather reductionist.

So, Axiom 12 states that you should always refer to, and tag, your COMPOSER and ARTIST with the composers full name, not just their surname.

So it's not Mozart, but Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart; not Britten, but Benjamin Britten; not Beethoven, but Ludwig van Beethoven.

Now, sometimes this can get a bit awkward. Is it really Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart when he regularly signed himself Wolfgang Amadé Mozart? Is it really Benjamin Britten when he was christened Edward Benjamin Britten? Is it Franz Joseph Haydn, or just Joseph Haydn?

Well, we can discuss angels and heads of pins all day on this one. My suggestion is that you call them by their full names, as they themselves used them, unless everyone else has disagreed with them! That is, we drop Britten's 'Edward', because he did, and no-one contradicted him on the matter. But we don't call him 'Amadè', because it's French, he was Austrian, and we're not that silly: since Peter Schaffer bought up all the shares in him, he's been Amadeus to man, woman and child of elves yet born. And so on: respect their wishes, but don't go overboard about it, basically

At the end of the day, the referee is -or should be- the New Groves Dictionary of Music & Musicians. And at a mere £1000 a pop, I'm sure you'll agree... that's it's not exactly a practical referee for most of us! Fortunately, I was able to pick up a cheap copy of the 1980 edition and have created a list of "valid" composer names from it, available for absolutely no effort and less money from here. Take your composer names from that list and you'll be doing it 'right'!

Using full names for composers can be alarming at first. You'll be searching for your Beethoven under 'B', when it's actually filed under 'L', or your Mozart under 'M' before realising it's now under 'W'. But you will swiftly learn ...and a side-benefit is that, I believe, you will come to feel more for, and sympathise with, Wolfgang rather than 'Mozart' or Ludwig rather than 'Beethoven'. There was a reason Edwardian public schools called boys by their surnames only: and it wasn't to increase the warm-and-fuzzies about their individuality and personality!

Axiom 13: Be Grammatical!

This axiom is aimed at anyone who Would Want To Tag Their Music Files As Allegro Con Moto, or Molto Espressivo Con Largamente.

You don't write In InitCap Mode Like That In Your Daily Life, so why on earth do you think it appropriate to do so when tagging music files?!

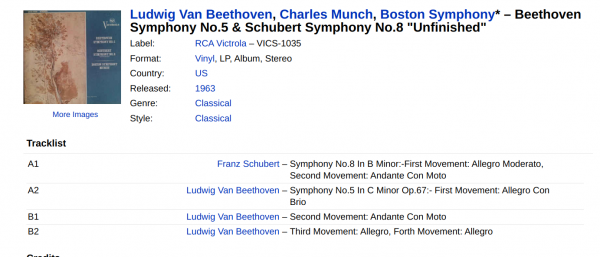

Well, I'll answer that: it's because the entire music industry is so fundamentally ignorant about the subtleties of classical music that they think that's how it's done. It's how you end up with pages from Discogs looking like this:

We'll draw a veil over the need to mention 'First Movement' or 'Second Movement' (when you've already got track numbers 1 and 2 to tell you such things!). Just look at the tempo declarations here: "Allegro Con Brio", "Andante Con Moto" and so on. It's appalling. It's the ill-educated peasant come to the Italian Literature ball. Do Not Tag Like This Ever.

Where it gets really stupid is in German, because in German a capital letter indicates not only the start of a sentence, but also the presence of a noun. So if you start throwing capital letters around, the German text suddenly becomes unintelligble. It would Mouse be Mouse as if Mouse every Mouse third Mouse word in Mouse English was a noun Mouse of some sort. It makes no sense. Please don't do it.

If you don't know how to write proper Italian tempo markings (and it can get complicated, I grant you), then at least recognise your 'Allegros' from your 'cons'. Know your adjectives from your prepositions. And if in doubt: look it up in reputable sources (such as IMSLP) that can show you the actual scores for free. What the composer has seen printed is probably a good indication of what the actual capitalisation should be.

Ultimately, of course, it's your private music collection and no-one else need ever see your degree of musical illiteracy if you don't want them to. But if you care enough about classical music to want to do the job properly -then Axiom 13 simply states: tag grammatically.

Axiom 14: Non English-speakers use diacritic marks. So should you.

Wagner didn't write Gotterdammerung, but Götterdämmerung. If you don't yet know how to use your computer to type accented letters quickly, learn how to. Given all the Germans, French, Spanish and Italians who have been writing classical music all these years, it's pretty essential to be able to do so, I think.

On Windows, you need to learn your foreign character 'numbers' (so that typing Alt+223 on the numberpad will give you ß and Alt+252 gets you ü, for example). Failing that, you can install the completely free WinCompose software, which allows you to type a special key, plus a punctuation character, plus a letter to achieve the desired result. Thus, right-alt plus " plus o gives you ö, and so on.

On Linux, that sort of WinCompose functionality is already built in to most desktop environments (though it might need enabling). Having enabled a 'compose key', you use it to initiate punctuation+character key sequences that end up producing properly accented characters. Thus compose plus / plus o yields ø, whereas compose plus s plus s gets you ß. And so on.

Sort of related to Axiom 13, too: don't just make one diacritical mark do duty for others, because you don't know how to type the right one! It is, for example, più moto not piú. Put the accent round the wrong way and you're now being ungrammatical in Italian!

There are limits, however, bounded by common sense. Whilst you, like me, might be fluent in Russian (or unlike me in Japanese), don't go tagging your Boris Gudonov recordings in Cyrillic or your Japanese song-cycles in Kanji! It is not likely to be useful ...but it does look a bit pedantic and too-clever-for-its-own-good! (If you're a native Russian or Japanese classical music listener, feel free to ignore this advice, of course!)

In short, Axiom 14 states that you should type foreign characters correctly when they appear, not make do with approximations or just miss them out and hope it doesn't really matter. The rider is: don't go overboard and start tagging things in non-Latin alphabets in their entirety.

Axiom 15: Don't be Obvious

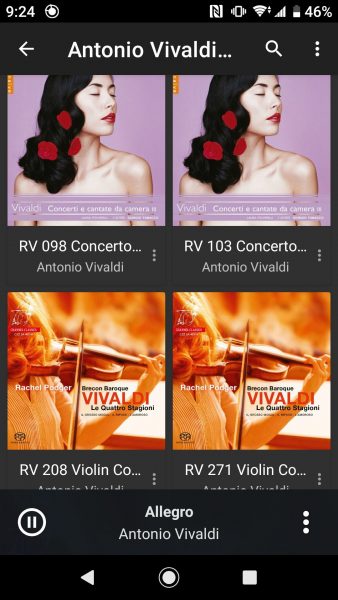

A Flute Concerto, by virtue of it being a Flute Concerto, is obviously for flute. And by virtue of it being a Concerto, it's equally obviously going to be for orchestra. So tagging it as “Concerto for flute and orchestra” is pointlessly redundant. “Flute Concerto” tells us everything we need to know in three less words. The main reason, indeed, for not getting too wordy (apart from it being slightly pretentious) is that whilst screen real estate is abdundant on a PC or laptop monitor, on many playback devices, screen real estate is very constrained and thus space is at a premium, to be used carefully. Consider one of those vacuum flourescent displays that show the track title, and scroll it from left to right, for example: you'll be waiting for Christmas before the word 'Flute' comes up if you've chosen to mention the 'Concerto for' bit first. On a smart phone, things can be even worse:

You tell me what is the primary instrument in the first two concertos mentioned on the top line here? You know it's a concerto of some sort -and if you know your RV numbers, I guess you could work it out. But if you don't, what sort of concerto is it? Basically, you cannot tell. On the bottom line of that screenshot, however, even apart from the album art giving you a pretty hefty clue that a violin is involved, you can readily tell, just from the text, that it's a violin concerto.

If brevity is the soul of wit, so it is also the heart of efficient tagging. Thus, Axiom 15 states that you shouldn't mention things which don't need mentioning because they're already implied: it just takes up room unnecessarily!

Other examples that come to mind would be tagging 'Otello' as 'Otello: An opera in 3 acts' (it's Otello: we already know by implication that it's an opera), or 'Symphony No. 9 for Orchestra and Chorus' (it's a symphony: we already know an orchestra will be involved, though the chorus is maybe a bit more of a surprise. But once we know the composer is Beethoven, even that element of surprise becomes something implicitly obvious).

A corollary to this Axiom is that if you do state something, state it using a word-order that provides as much criticial information up-front as possible. So 'Violin Concerto' is better than 'Concerto for Violin', because the crucial detail about which solo instrument this concerto was written for is being shunted off to the right in the second example, but is up-front and as left as it can be in the first. Word order is important: make the early words in a tag count for more than the later ones, basically.

Axiom 16: Album Art is important

This is sort-of related to Axiom 15, in that we've seen there how sometimes players don't display all the text we'd like them to display and that can leave us guessing!

But if a picture is worth a thousand words, then a good bit of album art can make up for a lot of truncated text tags! Apart from anything else, many of us will recognise and respond to the picture of a CD cover long before we've managed to read the text telling us what album it is: it's just the way the human brain is wired.

So, Axiom 16 states that album art is so important that you should strive to acquire it in good quality and at a decently-large size and then embed that art within the music file itself.

In terms of quality and size, I would say that 500x500 pixels is a usable minimum, but you should preferably be aiming for around 1000x1000 or bigger.

The little rider to this axiom in italics above is also critical: do not rely on files called 'folder.jpg' to act as your album art (as is commonly done on Windows, for example). Such independent files can be over-written, corrupted, deleted or somehow become separated from your music when you copy or move it around your file system. It is always much better to embed the album art into the FLAC file itself, so that it's essentially just another tag of data and has no independent existence. Most tag editors will allow you to subsequently re-export such embedded artwork back out to the file system as an independent file if you really need it later on, but all the while it's embedded, it's an integral part of the FLAC file, and it therefore automatically goes along for the ride when the file is moved, copied or converted. It's a much safer way of storing your album art, basically.

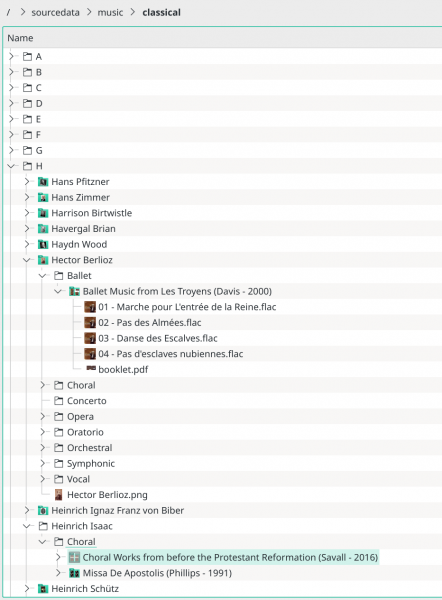

Axiom 17: The Physical Structure of your music library should match your Logical Structure

This is potentially one of the most important axioms, really. It's not so much to do with how things look, whether they are spelled correctly and use the right letters. It's much more profound than that.

Put simply, you have tagged your music with composer/artist, then genre, then extended composition name, and finally with track numbers and titles. Axiom 17 simply states that every one of those 'tags' should be matched in your file system by an equivalent level of folders.

It doesn't sound much, but it means that when navigated via your file manager, your folder structure should match your logical tag structure pretty much exactly. For example:

As you can see, I get to my composers via an 'initial letter folder', so the 'Harolds' and 'Hectors' are kept distinct from the 'Benjamins' and 'Igors'. But after that, it's pretty much the tag structure that was described in my primary key article: Composer -> Genre -> Album -> Track Number -> Title.

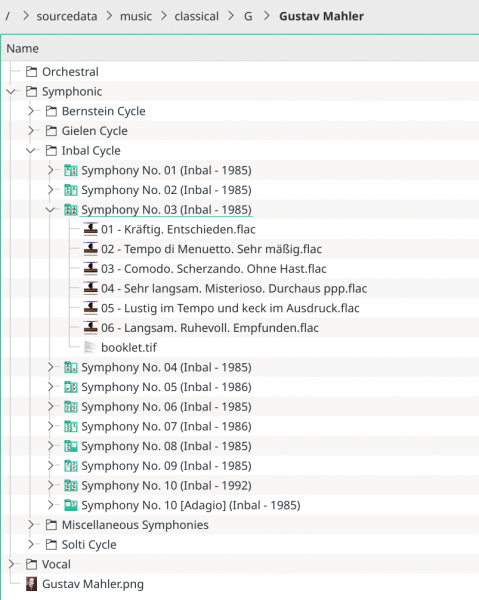

The reason for this is simple, but quite profound: if these elements make up the logical way to uniquely identify any given recording, then they should be capable of physically doing so as well: and there are definitely times when you will want to be able to switch between the logical and physical models. The logical model is great for media players that build libraries of your music, such as Strawberry, Clementine or Foobar2000: they abstract the metadata tags into a navigable 'music tree', where you navigate through the 'leaves' to get to the music you want to play. But sometimes, you will want to use your operating system's file manager to navigate through your music... and then it really helps if the physical 'leaves' are exactly where you're used to finding them logically.

Now, I do occasionally make exceptions to this rule, in that I sometimes add physical folder levels that have no counterpart in the logical world. Usually, I do this when the music quantities involved are otherwise huge, and the sub-division by genre isn't sufficient to break things out into small enough 'chunks'. For example:

I have so many Mahler symphony recordings that I've had to group them physically into folders by the conductor making the recording. There is no logical tag that mirrors this physical grouping into 'recording cycles', so here you're looking at a physical level of organisation that has no counterpart in the logical world.

But... it's rare for me to do this in the first place, and it works specifically this way round only. I do not have, nor would it be acceptable to have, for example, a grouping function by logical metadata tag that isn't reflected in the physical folder structure on disk.

Anyway, Axiom 17 states that whatever logical metadata you apply to your music file tags should be reflected in the physical organisation of your music on hard disk.

A corollary to this axiom is that you should never use the "/" or "\" characters in any metadata tag -hopefully for reasons that are rather self-evident! Since those characters mark the folder delimiter on Linux and Windows filesystems respectively, having them in your logical metadata risks creating extra levels of physical folder hierarchy if you ever use the logical data as the basis of a physical re-organisation of your files on disk. This is something quite a lot of tagging software permits: dbPoweramp on Windows does, for example. They take your tag data and use it to create folders on disk and move your music files into the appropriate folders for you, entirely automatically. Unfortunately, if in doing this they encounter a "\" or a "/" in the tag data, they may well create a sub-folder where you weren't expecting them to do so.

Thus, another corollary to Axiom 17 is that you should never use 'compound tags', split by "\" or "/" characters. Hence, a genre of "Orchestral/Symphonic" or "Choral/Mass" would never be acceptable. They imply a physical ordering that is at odds with the logical ordering, and Axiom 17 mandates the two should, mostly, be identical.

An Axiomatic Conclusion

So I want to draw breath at this point and remind you of all the axioms: 10 'hard-and-fast' ones and 7 'matter-of-taste ones, but they make sense anyway' ones.

Axiom 1: There are 8 tags you must have; all the rest are optional or downright not wanted

Axiom 2: Artist=Composer

Axiom 3: Comment=List of all performers, in a specified and consistent comma-separated order

Axiom 4: Genre=A one-word subdivision of a composer's works into usable chunks

Axiom 5: Album = Composition Name (Artist - Year)

Axiom 6: Performer = Distinguishing Artist's full name, with no punctuation or elaboration

Axiom 7: Year=Approximate (or known) year of recording, in four digit format, no specific dates

Axiom 8: Axioms 1 to 7 apply composition-wide; only 9 & 10 are track-specific

Axiom 9: Every composition should start with a track number 1

Axiom 10: Track titles are for abbreviated music facts, not dramatic details or musicological tours de force!

And:

Axiom 11: Never use a disc/disk/cd number tag. We don't use physical disks any more

Axiom 12: Catalogue by composers' first name, not their surname

Axiom 13: Be musically grammatical and never tag using InitCaps, nor lard your tags with non-musical information

Axiom 14: Use diacritics for all standard Western European languages. Approximating them or ignoring them isn't appropriate.

Axiom 15: Be musically literate: if a term (e.g., concerto) implies things, don't spell out the obvious (e.g., orchestra)

Axiom 16: Get good album art and embed it within your music files

Axiom 17: Let your physical folder structure mirror your logical ordering/grouping of music files, and vice versa

2.0 Some Discussions

The Axioms should clear up a lot of grey areas about how to tag, but some will inevitably remain. It is great, for example, to know what the ALBUM tag should have within it (see Axiom 5), but... what counts as a composition in the first place?! Additionally, it's nice that Axiom 1 says 'don't use ALBUM ARTIST'... but why not? So here are a few more generalised, fluid thoughts on matters tagging.

2.1 What's an Album?

So, Axiom 5 says 'that the ALBUM tag is to store the extended composition name'. And, by reading my other article about what is the primary key for recorded music, we learn that the extended composition name is composition name+conductor's surname+recording year.

But what counts as a 'composition' in the first place?

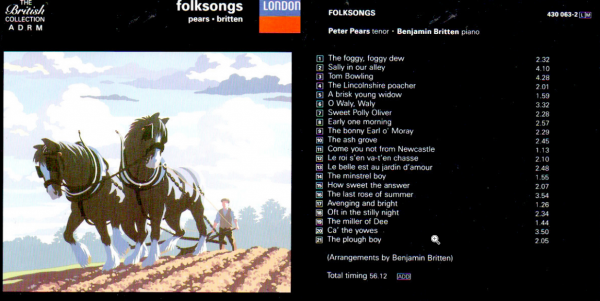

If Mozart doodled 3-bars of harpsichord one day as a 5-year old, does that really count as a "composition" in its own right? And what about this real-world example:

Here we have a CD containing a collection of folksongs 'arranged' by Benjamin Britten. He was a serious composer; these are a substantial body of work, produced over a period of several decades, and with nothing actually tying them together as an 'integral work of art', except for the fact that on this occasion Peter Pears is singing them all, accompanied by Britten at the piano. So, 'The bonny Earl of Moray' is definitely a composition in its own right (dating to about 1940, according to the Britten Thematic Catalogue). But does it count as an album in its own right, or not?

And as a recent correspondent wrote: what about the 555 Scarlatti sonatas? Do they count as 555 separate 'albums' or not? They are certainly 555 separate compositions, but do they count as significantly different from each other to warrant treatment as separate 'albums'?

In all these examples, I'm going to argue that Mozart's doodle, Britten's folk song settings and Scarlatti's sonatas do not count as significant compositions in their own right, sufficient to warrant them being tagged up as separate albums. But: there is no hard-and-fast rule about this.

I'l give you yet another perspective from personal experience: the works of Percy Grainger. When I first ripped his complete works on Chandos, I took every composition as an independent work (and hence tagged up as a separate album), so long as it was longer than a few minutes (fragments of music are seldom going to count as 'albums', after all). So, as long as it was over about 5 minutes long, it got ripped as a separate album. But once I got a bit familiar with Percy Grainger's music, it soon became abundantly clear that it was incredibly ...er.... "similar"! There really wasn't a lot to distinguish 'Colonial Song' from ' Shepherd's Hey', in one's head: they were both nice pieces, but they were -fundamentally- merely bricks in a wall of Graingerism. They had no independent significance, despite their individual lengths sometimes ranging from 8 to more than 10 minutes. I think if I was more 'into' Grainger, I would be able to keep each piece separate and distinct in my head -but for me now, there was no point in regarding even lengthy compositions as separate works (and hence as individual albums). In fact, the proliferation of lots of little pieces by Grainger meant I seldom chose to play him: in my music player, there was this huge list of Grainger things and choosing any one of them made about as much sense as choosing to listen to any other. So I generally didn't bother at all, which is a shame.

So, recently, I re-ripped the 19 CDs of his complete works into 19 separate 'albums', each comprised of a dozen or more of his 'compositions', definitely breaking the nexus between composition=album. I ended up with 19 'sets' of Grainger, rather than about 200+ compositions by him -and it's much easier to settle down for an hour of Grainger than for 6 minutes of this, then select another 8 minutes of that... and so on. By re-aggregating Grainger's music, I've made choosing it to listen to a lot easier and pleasanter. I listen to him much more now than before as a result.

My point, really, is that there's no answer to 'what counts as an album', because it depends on a number of factors, such as:

- length

- significance

- uniqueness

Anything less than 5 minutes in length really needs to excel in the unique and significant stakes for it to be worth regarding as an 'album' in its own right. But then it all depends: if a piece of music has taken on a life of its own as a singularly well-known work, it might count as an album all on its own. It's why Grainger's Handel in the Strand is still a 'standalone album' in my collection, and not subsumed into the 19 other 'Grainger Orchestral works' albums I've got catalogued.

Uniqueness is even harder to define and your own personal experience will affect the outcome. For me, something like Britten's Festival Te Deum is a unique piece of composition (since I sung it in Lugano Cathedral!) and nothing would persuade me to combine it with a pile of other works and call it 'Britten Choral Works' as an album, for example.

I think the fundamental question to ask, really, is "do I think of this uniquely and separately and of intrinsic importance. Or does this piece only gain its significance because it's part of a combination of other pieces?" If it's capable of standing on its own feet as a significant work of art, catalogue it separately as a distinct "album". If it only makes sense in the context of a lot of other pieces, catalogue them collectively as a single 'theme' album.

So looking at those Britten folksongs earlier: some of them are quite long. Look at Tom Bowling for example: over four minutes long. But does it get its 'significance' from being a substantial composition by Britten over four minutes in length, or because Peter Pears is singing it as part of a 21-track combination of British folksongs? In my view, it's the latter: and therefore, I'd tag the lot as a single 'British Folk Songs (Britten - 1963)' album.

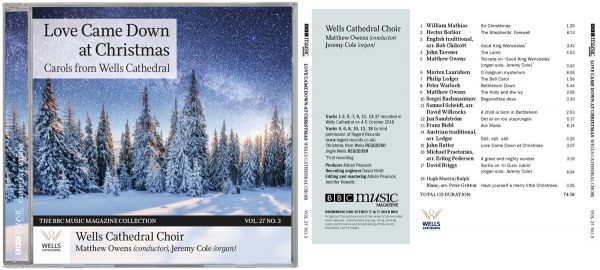

Here's another example of the same sort of problem.

This is an example of what I'd call a 'mood CD'. You get 'Medieval Christmas' albums; or 'Spanish Renaissance Wind Band' albums; or, as in this case, 'Music for Christmas' albums. Mood CDs, as this one does, often have quite substantial compositions from different individual composers, all mashed together to create an overall 'theme' or 'mood'.

So: look at track 6: Morten Lauridsen, O magnum mysterium, lasting for a whopping 8 minutes. Or Peter Warlock's Bethlehem Down, lasting for nearly 6 minutes. These are not trivial compositions -and in at least one case, not by trivial composers, either. Don't they count as 'separate compositions' and thus rippable as separate albums?

Well, they could. And if you made that call, I couldn't complain, really. But when I came to rip this CD, I decided that none of the pieces really had the heft to stand on their own. Their significance was derived from the cumulative impact of them being part of a wall of Christmas-sounding music. Rip them out of that context, and they would lose significance.

Therefore, I ripped the entire CD as a single album, and attributed it to a composer called 'Compilation'.

And this is the only instance in which music may be legitimately attributed to a non-existent ARTIST or COMPOSER.

Mood CDs will always trip over this fact. It's why I try to avoid buying them! But where a symphony belongs to Mozart, or a concerto belongs to Haydn, a mood CD will generally belong to someone called "Compilation".

Now, it happens that the TITLE can then contain details of the actual composer of each piece within the mood CD. That's fine. But I wouldn't attempt to elevate any of the compositions on this 'Christmas Swoon CD' onto the same plane as a Beethoven Symphony or a Bach cantata.

2.2 Why no ALBUM ARTIST?

The ALBUM ARTIST tag was created for non-classical music listeners to be able to deal with 'compilation' albums, where tracks on the same CD would be written or performed by different people. In these cases, they'd use ARTIST to say who was performing a specific track (and it would change as the tracks changed) and then use ALBUM ARTIST to say the disk belonged to 'Various Artists'.

We have no equivalent concept of this sort of thing in classical music, however. Though we buy CDs, which may package the works of multiple composers onto one disk, we do not deal with the CD as a whole, once we've ripped it -because, as separate digital files, the separate compositions can be housed in unique folders. Each folder then becomes an album, and each album is then composed by a single composer. We may therefore apply the composer's name to the ARTIST tag, and can do so across the entire 'virtual album': it doesn't change on a track-by-track basis. We therefore have no need for an over-arching 'Album Artist' to group things together, since our 'albums' are grouped by a proper composer's name already.

The only time you might argue we need Album Artist is, therefore, when discussing the sorts of 'mood albums' I've discussed earlier in Section 2.1: attribute WIlliam Mathias, Hector Berlioz, John Tavener and the rest to ARTIST and then say the ALBUM ARTIST is 'Compilation'? Well, personally I'd set ARTIST to 'Compilation' and mention Matthias, Berlioz and the rest in each track's TITLE... and there's a technological reason for doing this. Putting it bluntly, you never know what a media player will display when it has both an ARTIST and an ALBUM ARTIST tag to worry about.

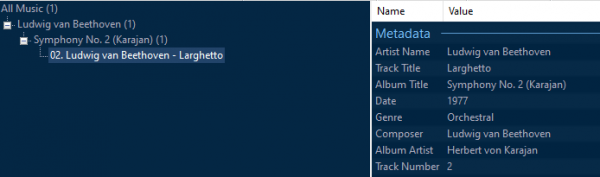

By way of example, consider a track of Beethoven's music which has "Ludwig van Beethoven" in the ARTIST tag and "Herbert von Karajan" in the ALBUM ARTIST tag (quite a lot of classical music listeners seem to think conductors are a good idea in the ALBUM ARTIST tag, so let's just run with that for now).

Here is how Foobar2000 deals with this twin-tagging strategy:

Basically, it ignores it. Over on the left panel, the music is attributed to Beethoven and Karajan is nowhere to be seen (except by surname in the extended ALBUM tag). The ALBUM ARTIST tag is certainly there: you can see it over on the right-hand side of the display, one line up from the bottom... but the main display panel on the left is entirely oblivious to its existence.

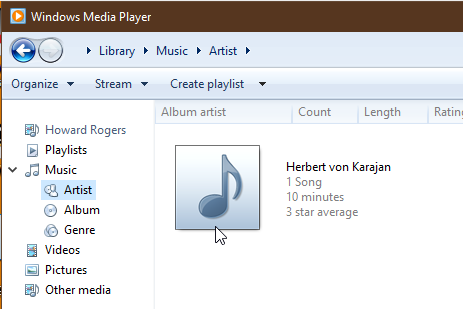

But take a look at what Winamp does with the exact-same file:

This time, the work is by Herbert von Karajan and you can't even tell it's a piece of Beethoven at all! So, use a different music player and now get ARTIST ignored and ALBUM ARTIST displayed. Finally, let's try another WIndows music player, in case Winamp is just being 'weird'!

Here's Windows Media Player:

Even though I've clicked 'Artist' in the left-most pane, it's displaying 'Herbert von Karajan' as the person of interest in the music display area over on the right. Once again, the fact that Beethoven is involved is nowhere to be seen.

The short version of this is that a tagging strategy is a long-term thing (you don't want to be re-tagging 60,000 files 20 years after you started collecting them!): what you decide to tag today should be capable of doing duty for the foreseeable future, no matter what music devices you use and stop using; no matter what operating system you use or switch to; no matter what music playing software is hot today and cold tomorrow. And, fundamentally, if you tag both ARTIST and ALBUM ARTIST, it becomes a matter of pot-luck what will actually be displayed. One software update later, or a switch of operating system environment, and bang! What you're used to seeing displayed may change completely. This sort of randomness is not desirable, and apart from the fact that we don't need an ALBUM ARTIST in classical music, it means that you simply shouldn't use the ALBUM ARTIST tag at all.

2.3 Composer Names

I'm never quite sure why people are so reluctant to think 'Wolfgang' not 'Mozart', or 'Edward' rather than 'Elgar'. But they seem to, and I think that's a shame and why Axiom 12 states that composer names should be entered in full and not just as surnames.

I want to add at this point, however, that what people think of as 'composer names' has frankly astonished me in the past. You will see serious advice, seriously offered, by sincere people, to tag Artist (and hence Composer) as, for example, BRITTEN, Benjamin (1913-76). Or "Bach, JS". Or "Mozart". So I want to be very clear about this: composers have natural names. Use them in full. Use them with normal capitalisation. But leave out material that's best read in biographies.

By this, I mean that the correct tag for works by Benjamin Britten is "Benjamin Britten". By Bach, it's "Johann Sebastian Bach". By Mozart, it's "Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart". Natural names, naturally spelled and using natural word orders!

Natural word order is important because there's absolutely no need to mangle word order in order to get a computer to find works by Britten, or to sort them all together. A computer will find 'Britten' whether you've entered it as "E.B.Britten" or "Britten, Benjamin" or "BRITTEN,Benjamin" or "Britten, Edward Benjamin" or even as "Baron Britten of Aldeburgh". There's thus simply no need in the digital age to use the reversed word order beloved of librarians and old-fashioned card indexes, nor to introduce capital letters where none are ordinarily required.

I strongly recommend you use a composer's full name as ordinarily and commonly used by the composer himself. Thus, technically, it's Franz Joseph Haydn -but neither Haydn himself, nor his family, nor his friends ever used the 'Franz' bit: it was simply a custom of the time to give a baby two saints names as first names and then to forget one of them. So it's Joseph Haydn to you and your musical collection, just as it was to Papa Haydn himself. For the same reason, it's not Edward Benjamin Britten. And although Mozart commonly called himself 'Wolfgang Amadé Mozart', the 'Amadeus' usage is now so commonplace that it would be churlish not to use it. Whatever you do, don't, for heaven's sake, start using his actual baptismal names: Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart is a mouthful too large to swallow!

For the same reason, don't use a composer's titles or honorifics. Vaughan Williams was immensely proud of having obtained a doctorate in music and accordingly frequently liked to be addressed (and signed letters) as "Dr. Vaughan Williams"... but don't go calling him that in your music library. Edward Elgar, for the same reasons, loses his knighthood. Titles and honorifics go, really, for two reasons: they disrupt the expected sort order (you expect to find Elgar's music amongst the other 'E' entries, not the 'S' it would be filed under if he was tagged as 'Sir Edward Elgar'. Secondly, most people simply don't think of them when they bring a composer to mind. People think of 'Vaughan Williams' or 'Ralph Vaughan Williams' or 'Ralph'... seldom do they think of 'Doctor', let alone of the 'O.M.' honorific he was entitled to use after 1935. I suppose that's the third reason for missing them out, too: often, a composer only got to use a title or honorific for part of his life. Poor Ben Britten was a Lord (or Baron, if you prefer) for only the last six months of his life, after June 1976. Tagging stuff he composed in 1936 with 'Baron Britten of Aldeburgh' is anachronistic (and pretentious!)

I will grant that there a couple of exceptions to this general 'no titles' rule: Lord Berners gets catalogued as Lord Berners, because no-one really knows him as anything else. His real name was Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt-Wilson, but not only is that a mouthful, no-one will have the slightest clue who you're talking about if you use it. So Lord Berners gets to keep his title. Sir John Blackwood McEwan also retains his knighthood, because the title is always and invariably used when discussing him or his works (Britten's baronetcy isn't, in contrast).

To try to help standardise on what I consider to be 'correct usage' of composer names, I've prepared a list of names in another article, which I recommend you follow at all times. It's not exhaustive (that is, it doesn't claim to list every single composer who has ever lived), but it is aiming to be prescriptive (that is, if you want to tag music by Janacek, for example, it aims to prescribe the fact that you should tag it as Leoš Janáček, complete with all the appropriate diacritic marks).

Following this advice will, of course, mean that your Mozart music will now be filed under W; your Prokofiev will end up under 'S' and your Beethoven will be filed under 'L'. This is undeniably true and some people seem to hate this ordering. I can only suggest you persist: it's actually good practice to get to know your composers well, and getting to know them by their first names seems the least you can do in that regard! Remember, too, that the computer is your friend: whilst your Mozart might be listed under 'W', you can always find it using your media player's search capabilities and typing in just 'Mozart'.

Remember, too, that everything I've just said about composer names applies to the Artist tag too.

2.4 Searching by COMMENT

I've had people complain about my Axiom 3 (that all performer details should go into the COMMENT tag) on the grounds that the data is not usable or discoverable there. This is simply not true for any music player with which I'm familiar, however. Even iTunes can search the COMMENT tag if you first make it visible as a displayed column on the main playlist view.

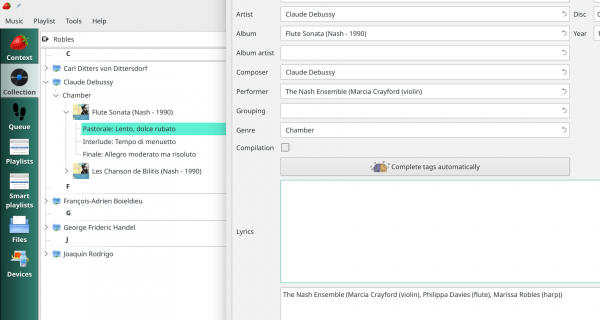

As a case in point:

There seems no obvious reason why Debussy's Flute Sonata should be listed when I search for 'Robles' at the top of the screen, over on the left. But an inspection of the metadata associated with that music, over on the right, shows that Marissa Robles was the harpist on that particular recording. She presumably harped on the Handel, Rodrigo and Dittersdorf recordings, too (she did, I just checked!)

So, everything you put into the COMMENT tag is most definitely usable by every music player on the planet -and if it's not by the player you happen to prefer, it's time to invest in some different music-playing software!

Of course, for COMMENTs to be useful, the data in them needs to be entered in a consistent manner. If you tag one recording up as being performed by the 'Berlin Philharmonic', don't expect to find it if you start searching for "BPO", "Berlin Philharmoniker Orchester" and so on. The Vienna Phil and the Wiener Philharmoniker might be the same thing to you and I, but they are completely lexigraphically different to a search engine. So, above all else, be consistent.

3.0 Conclusion

I get that when you read this long list of 'axioms', it can look and feel pretty daunting, if not petty and trivialising. After all, you listen to classical music because you like the music, not because you like observing nit-picking rules. I can only urge you to imagine what it would be like trying to 'like' the British Library if they didn't have a damned good index card system that references every book they own, and let's you find one easily by simple organisation of data. A good card index makes literature discoverable. A good, consistent and logical approach to tagging your music files makes the gloriously diverse world of classical music discoverable for all time thereafter, too.

I commend these 'rules' to you, to apply in your own tagging jobs, not because I like petty rules but because I know applying them has made my extensive music collection highly usable over decades, in other words.