Last Tuesday, myself and Mark drove off at the crack of dawn from Nottingham, en route to my favourite place in the Universe... Aldeburgh.

Last Tuesday, myself and Mark drove off at the crack of dawn from Nottingham, en route to my favourite place in the Universe... Aldeburgh.

We had an appointment with someone at 1pm, which I'll get to. But I never like to leave things until the last moment, so I insisted we leave at 6AM, which meant -with a break for a cooked breakfast- we ended up arriving in Aldeburgh at 10.30, rather earlier than anticipated!

We also discovered that you can park on the sea-front for absolutely nothing, which was the second surprise of the morning 🙂

Naturally, a long walk up the beach ensued (photos are inevitably available!), and then a quick pint at the pub immediately adjacent to the Aldeburgh Fish and Chips shop, which opened as scheduled at 11.45am. A small cod-and-chips purchased from there represented (perhaps surprisingly, given my love for the place) my first-ever piscatorial purchase from that establishment in the 39 years I've been going there! We hot-footed it to a nearby stretch of beach to consume the food -and it was at this point that it became Mark's turn for a surprise, as one of the local population of seagulls decided that the fish-in-batter looked a lot better in his mouth than in Mark's. Neither of us saw it coming, but I heard a distinct 'thud' as it basically whacked Mark's head in a full-speed descent attack! The battered fish leapt from Mark's hands... and was immediately captured in-flight by the same gullish thief.

We laughed about it for the rest of the day -but it was a full-on head-thwack by a distinctly plump and adult seagull, and we didn't get to eat much of the fish and chips in the process, either 🙁 The little I was able to eat before the inflight robbery was, however, delicious and properly cooked (so many English chips are pale, yellow and practically raw... these ones weren't any of those things!)

Anyway, with mucky fingers and (in Mark's case) slightly bruised and battered head (and ego), we wandered back to the car, taking in an ice cream on the way. For it was time for our 1pm appointment... with the archivist at the Red House Library. (Incidentally, finger-feeding on oily fish and chips, plus dripping ice creams, is not really recommended before a visit to a historical archive with precious documents in the vicinity! Fortunately, a thorough hand wash en route provided appropriate remediation).

And thus it was at a little before 1pm we were able to waylay the archivist (Judith Ratcliffe) at the entrance to the archive, apparently as she was just off for a quick lunch break. She immediately dropped all her plans when she knew who we were, however, and took us into the Archive Reading Room.

The purpose of the visit was for me to hand over my correspondence from Peter Pears from 1983, when I had written to him to ask if I could visit him and talk about music and Benjamin Britten -a request he granted in August of that year. I took scans of those letters before I gave them to the archive, of course. There is nothing in them that will change history or provide profound insight into the nature of Peter Pears -but they seemed pleased enough to have them, in part because one of them was written in bright pink felt pen. That seemed to amuse the archivist, since it was apparently confirmation of his tendency to the 'unusual' when corresponding with people. They also indicate what a down-to-earth and unpretentious man a great artist in the last years of his life could be, towards a gauche 19 year-old nobody who had the temerity to intrude on his time. So, they graciously accepted the letters into the archive, and I got a receipt to say I'd donated something to them.

And then I got the treat of my life, as Judith fetched the manuscript short score of Britten's last opera, Death in Venice, and laid it out on the reading room desks for me. I had asked, by way of a favour, if I might be permitted to see this in return for the donation. I had expected a clean room, air conditioning and gloves... but no, the many pages of short score were just laid out on the table for me... and I was allowed to flip my way through it as I liked!

I had specifically asked to see the bit of the score where Aschenbach declares 'I love you!', at the end of Act 1... but the short score stopped peculiarly just short of this crucial moment. That's when Judith called in Dr Nick Clark, the Red House librarian, and he swiftly rectified the situation by finding the folder containing the second part of Act 1! So I got to see -and touch!- the crucial moment after all.

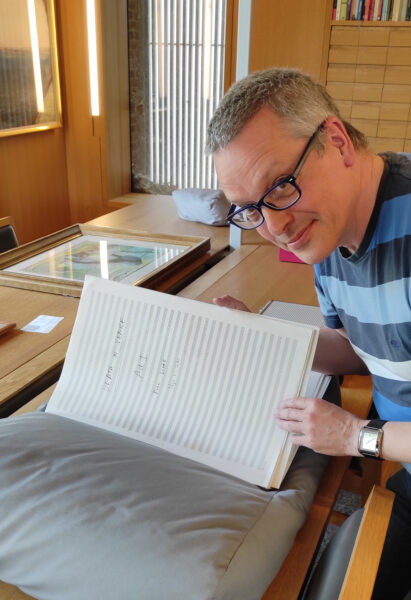

Then Nick dropped a bombshell: the full score of the opera was not out on loan, as Judith had thought. He could find it easily enough.. and he duly did! I therefore found myself experiencing the thrill of handling and flipping my way through the pages of the full score of Death in Venice, too. Nick was particularly keen that I see the extraordinary orchestration of the final bars of the opera, as Aschenbach dies and the gamelan-like orchestra ascends to the stratospheric heights. It was wonderful. And I could hear all the notes in my head, for the score was straightforward to read and follow, clear and clean.

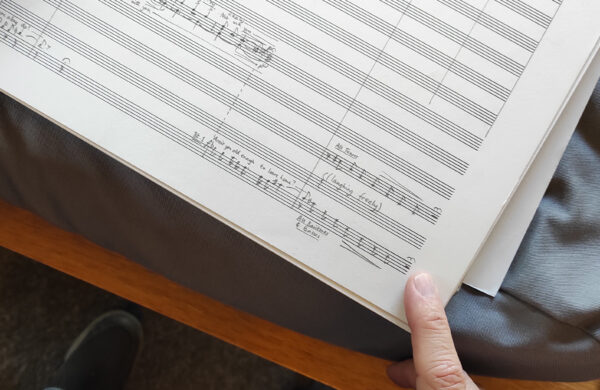

Nick and I then went on a bit of a 'hunt the Curlew Sign'! The Curlew Sign is a strange bit of musical notation invented by Britten, indicating a sort-of flexible pause, a point in the score where 'the performer must listen and wait until the other performers have reached the next barline or meeting-point'. I knew there ought to be some somewhere in the Death in Venice score, but I couldn't remember where! So Nick and I hunted for a bit, until we got lucky and found one (well, two actually), right at the end of a page! That was fun!!

Another moment of jollity: the front page of the full score is written in a peculiar mix of pen, ink and something looking suspiciously like felt pen. As Judith put it, "Ben must have grabbed one of Peter's felt pens that happened to be nearby": my own addition the archive proved Peter's fondness for such writing implements, after all! That sort of thing was not Britten's usual style, shall we say? 🙂

A couple of things came to mind in all this. First: these were not 'pages' of score. They felt more like cardboard or stiff card! They were very heavy paper, basically -and, as I was able to discuss with Nick, probably the reason for this is the fact that so many people had to handle and work from these pages after they had been written. The full score, for example, had been retrieved from the vaults at Faber and Faber (Britten's music publishers in the latter part of his life), which gives you an idea how this precious document had to be handed around, so that the published score and parts could be engraved. Goodness knows how many hands were involved in the engraving process -but you clearly wouldn't want the music written on flimsy, thin paper at that point!

Another thing that was obvious: Rosamund Strode's fingers were all over the work (and, fittingly, there's rather a nice pencil sketch of her on the Reading Room wall: she deserves it). She was Britten's assistant in the 1960s and 70s, and one of her jobs was to take the short score (basically, all the music fresh from Britten's brain, but on just two staves, with mere indication of orchestration where needed) and then take a bunch of music paper and mark it up with staves for full orchestra, and with bar-lines pre-laid out. Britten would then fill in the full score after she'd already marked up the paper. A lot of the text in the score (i.e., the actual libretto, dynamic markings, tempo indications and theatrical directions) would thus end up in Rosamund's hand (easily identifiable, because it was so neat and precise). But the notes were all unmistakably in Britten's equally clear and precise hand writing.

That made me realise something else about the composition process. I don't know if I'm alone in thinking it, but I expect many people imagine a composer sitting at the piano, waiting for inspiration, then jotting down the notes and thus creating a wonderful work of art through sheet genius. What I realised from what I was handling was that, actually, Britten was really more of a musical composition factory: the process was precise and meticulous and involved a sort-of production line that required many people to chip in to achieve the final product. He didn't just 'write Death in Venice'. He wrote a sketch of it; weeks or months later, with Rosamund's help, and probably with the input of a cast of hundreds, he turned the sketch into a full score. Then he had to proof-read the engraving of that, and correct it. And only at the end of all that toing-and-froing do we end up with an actual composition in a finished state. Composition is a process, basically, not an event.

I probably already knew this in my brain, but the sheer scale of the scores that were laid out in front of me brought the matter home in really sharp focus for the first time. How Ben was able to pen something in two staves one day, and then remember what had been going on in his head months later when it came time to fill in the full score details of that same part of the work, I have no idea. But by looking at the short and full scores, one definitely saw evidence that the composition process was something extended, lasting for months and years, and requiring the ability to hold such a deep conception of a piece for all that time it took to go from sketch to score. Never mind, too, that it required others to be involved in the process of production (such as Imogen Holst in the 1950s and Rosamund Strode thereafter): they've got to understand you, your habits, your handwriting, you thought process. They have to anticipate if they are to assist effectively. The evidence before my eyes that composition was a process of 'manufacture', not a moment of mad inspiration, made it all the more remarkable for me.

Judith mentioned in passing that most enquiries made of the archive are answered by email, using scans and other reproductions of the source material. In the case of most of Britten's scores, for example, researchers are generally directed to use the microfilms of the scores (which were prepared by the same Rosamund Strode who was deeply involved in the production of the scores themselves: she must have worked her socks off in those years!) Basically, almost no-one gets to handle the originals, except in very rare circumstances. So: you get an idea of how special I felt as we took our leave of our hosts for the afternoon.

In short, for this life-long fan of Britten's music, I had just been allowed to drink from the Holy Grail. Or touch the Holy Tablets from Mount Sinai. Or... well, pick your analogy of choice. It doesn't get a lot better than this, and I fundamentally doubt there will be as special a moment in my life ever again.

The joy of the last couple of days didn't end there, either. For a start, I now know that the reading room of the Archive is open to anyone, almost at any time. The room is lined with books about Britten, which can be freely accessed: in all my previous visits, the reading room had been used as the space for special exhibitions and so on, and there was never any indication that the adjacent books are allowed to be handled by mere mortals! I had thus never realised you could just sit down in there and start reading! So that was a nice discovery on its own -and if you are ever visiting Aldeburgh for a short break, I can't think of many nicer places to while away a couple of hours! Never forget, too, that the grounds of the Red House are about 5 acres in total and are gardened in a beautiful, wild, country-cottage kind of way. Nothing too manicured, but all of it stunningly beautiful. I guess mid-Winter might not be so nice, but a Tuesday in early May was just glorious! So there's yet another way to spend a couple of hours, too!

Whilst waiting for Judith to retrieve the Venice short score, I happened to pick one book off the shelves which I didn't recognise as being one I already owned. Turned out to be a memoir of Steuart Bedford, called Knowing Britten, and within 30 seconds of beginning to read whatever page I happened to have opened it at, I realised I had to own it. So an order went in to Amazon that night; the book was delivered late Wednesday and I've now just finished it, Thursday afternoon: it was that good a read! Steuart Bedford, of course, was the young conductor whom Britten entrusted to conduct the world premier of Death in Venice, so the aptness of the random discovery of that book on the reading room shelves was rather wonderful 🙂

On the journey home, we stopped overnight at Beccles (near Norwich), and roaming around there, we chanced upon a hardback copy of Journeying Boy - The Diaries of the Young Benjamin Britten 1928-1938 in a rather nice second hand bookshop, for the princely sum of £2 (original book jacket price: £25). So that was another treasure snapped up!

I then came down with something akin to 'flu (but no cough, nor lack of taste nor smell, so not Covid!) and thus had a rather miserable journey back home later that day.

Nevertheless, regarding this Aldeburgh visit as a whole, and in the words of Howard Carter, in reply to the question '[did] you see anything?', the answer is simply: 'Yes, wonderful things'.

PS. The Britten manuscripts are still under copyright. Death in Venice, specifically, is still the copyright of Faber & Faber, for example -and never mind the Britten Estate or the Trustees of the Red House! Though Judith was more than happy for us to take photographs of our visit, I assured her that they would not end up on 'social media'. I'm not sure if a personal blog counts as social media, but in the interest of sticking to my side of the bargain, I'm uploading only two photos from the visit. One shows me holding the full score, but reveals no music at all, just its (rather iconic!) front page. The other shows me alighting upon the reclusive Curlew Sign... and I hope that as it displays only a single, small piece of musical notation, its inclusion here will count as fair use and in line with the undertakings we gave.