1. First obtain a German Text

The Bach Cantatas translation project starts by acquiring a German text for a particular cantata that conforms to what is generally regarded as 'the standard text'. I do this by first fetching the German text from the Bach Digital website.

To try to ensure that the text so obtained is accurate, I then also acquire the equivalent German text from the Bischof website.

I run both texts through a text comparator (there are various ones available on the 'Net, such as this one, though I generally use the diff utility as I use Linux as my operating system and that ships with most distros by default. Where the comparison flags up differences (of punctuation, spelling, even occasionally of words), I turn to my edition of Alfred Dürr's The Cantatas of J.S Bach. Whichever version of the text agrees with Dürr's German texts then regarded as the 'correct' text.

Of course, if both Bach Digital and Bischof agree, but are in error, the text comparison would not flag an issue and a non-Dürr-ism might squeak through. I try to prevent that happening by doing a final visual check of the obtained and corrected text against Dürr's text.

2. Obtain a 'global' English translation

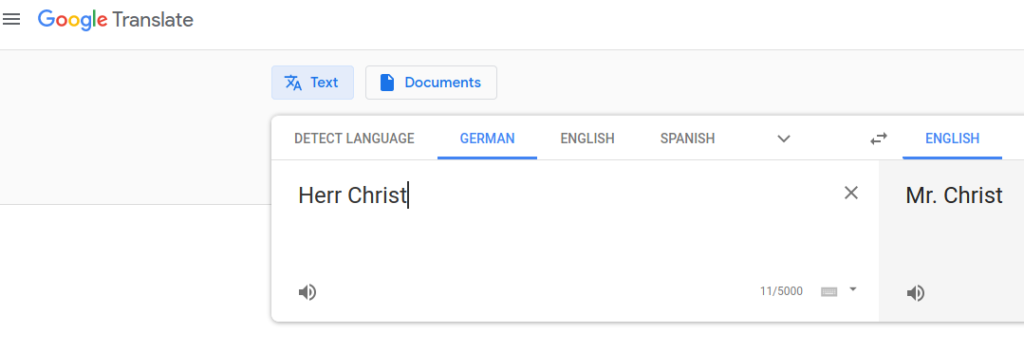

Once a staisfactory German text has been obtained, I paste it directly into translate.google.com and obtain a whole-cantata English translation. The translation so obtained will always and without exception be terrible, but it's a 'skeleton' on which to hang 'decent' text later on. Hilariously, for example, Google will always translate 'Herr Christ' as "Mr. Christ", rather than the more usual "Lord Christ":

...which gives hours of fun, but not much enlightenment!

3.0 Prepare an English movement-specific translation

With an English(ish) text broken up into separate movements, I tackle each movement in turn, going back to the original German and working out a hand-carved English version. I compare this to the Google translation to make sure I'm not going wildly off-piste.

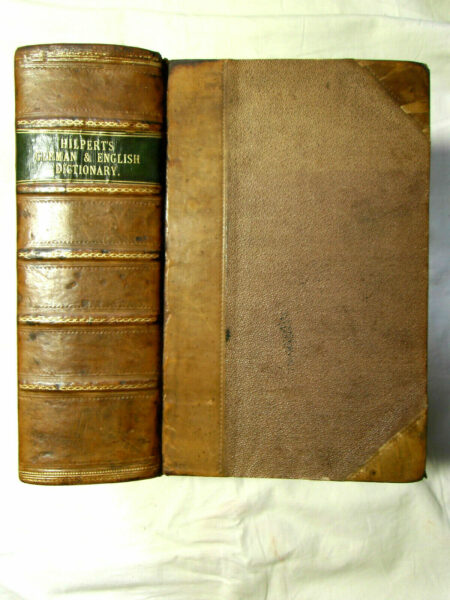

Essential tools at this point of the game are my 1853 German-English dictionary:

I can of course (and do) consult online dictionaries, too: I find the Reverso one quite useful, for example. But a modern dictionary can often be a little less than useful when trying to translate 18th Century (or even earlier) German, in the same way as a modern Oxford English Dictionary would be a bit "off" when it came to explaining some words that Shakespeare or Chaucer may have used. So by using a dictionary that appeared only 103 years after Bach died, I hope to minimise the sorts of confusion that would arise when translating an 18th Century idiomatic expression using a 21st Century dictionary. Ideally, I would have used an early 1700s German-English dictionary, of course, but they are as scarce as hen's-teeth!

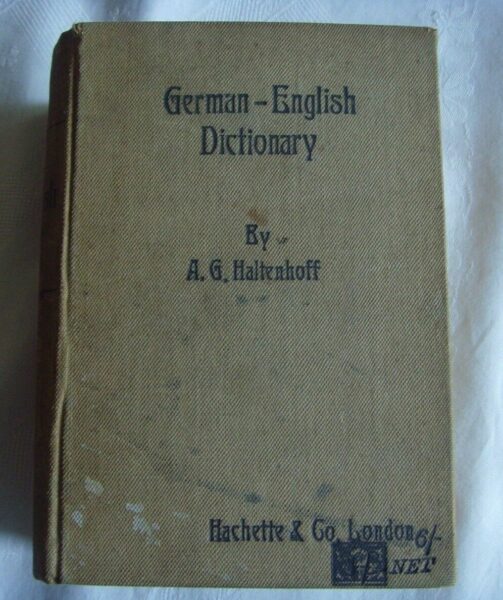

Occasionally, the Hilpert's is silent on a translation question, so then I consult my 1902 Haltenhoff:

If either of those fail, it's a trip to the online Reverso dictionary and fingers crossed.

4.0 Compare the whole translation to others

At the end of the movement-by-movement translation process, I have a whole-cantata English text, which I like and think acceptable. I read the whole thing over, several times and usually over several days, until I'm happy with imagery, punctuation and accuracy. Little tweaks and twiddles will be done to sharpen the translation up at this point until I'm happy with it.

Then I read other people's translations. I read the Dürr English translations, for example, actually done by Richard Jones. I may read the Emmanuel translations. I will usually also read the Bach Cantatas interleaved translations (for example, this one), usually done by Francis Browne. At any point during these readings, I may note that I have picked wildly different phraseology to these others. If so, it's back to the dictionaries to determine whose wording is more accurate. I may adjust mine as a consequence, or I may decide the others are wrong and so stick with my original thoughts on the matter. During a reading of these other versions, I will check that my translation isn't too wordy or "angular" compared to others: if they have a nicer or more compact or more poetic way of expressing a thought than I came up with, I may adjust my text accordingly. Generally, however, I'm going to find the Dürr and the Browne, especially, highly "functional" but seldom "literary", so that's not going to happen very often. 🙂

5.0 Prepare the Translation Page

With an English translation I'm happy with to hand, I then create the appropriate page for the cantata in question. This means:

- Finding a full-score PDF of the cantata that is in the public domain that I can copy to my website

- Finding whereabouts in the Bärenreiter "Neues Bach Ausgabe" the cantata's full score can be accessed (the 'NBA numbers' attached to each cantata record)

- Finding where on Amazon.co.uk the relevant cantata can be purchased in Suzuki's recording and linking to it

- Preparing short audio extracts of the entire cantata, uploading the resulting preview tracks and creating a playlist of those tracks

- Making fair copy of any notes I may have scribbled down when making the translation if those notes highlight a point of dubious meaning or syntactical complexity or anything else worth thinking about

- Making sure the German and English texts flow side-by-side in a line-by-line matching fashion

At some point in the future, this will also involve collecting a lot of historical and musicological information together about each cantata's origins, performance history and music structures and techniques, to create full 'Analysis' sections, but that's a huge future project that I'm not getting into at this point and will have to wait until all cantata translations are complete. The first 23 or so cantatas have sketches for what these analysis sections might look like in the future, but I have not prepared any more at the time of writing.