I've been having an interesting discussion of late, over on the Talk Classical forums.

I've been having an interesting discussion of late, over on the Talk Classical forums.

It began life as someone saying they still preferred to use physical media for their classical music listening pleasure rather than any of the streaming, YouTube or similar 'consume-but-don't-own' musical options available these days.

I agree with that sentiment in one sense: I hate streaming music. If I don't own it, it doesn't really 'count' in my mind. If I own it, I curate it and maintain it and make sure it's metadata is accurate and so on; if I merely 'consume' it, I have no idea whether all that's being done correctly or not (but can be pretty confident that as it's classical music we're talking about, it won't have been!)

So, though this site and my personal preferences are all about ripping music off a CD, I get and agree with the 'ownership' angle of the original proposition.

But then the discussion morphed a little (sorry: it was probably my fault!). The trouble I have with CDs is that they split music into multiple tracks -and we then tend to rip them per track, and thus we end up with digital music players that can play the Adagio from that symphony, and the Presto from that concerto.... and we think nothing of it, because that's just the way it's always been with recorded music, right?

Wrong!

That's a photo of my highly-prized and beloved 78rpm first edition of Benjamin Britten's 1943 masterpiece, Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings: the recording was made in 1944.

That's a photo of my highly-prized and beloved 78rpm first edition of Benjamin Britten's 1943 masterpiece, Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings: the recording was made in 1944.

The Serenade has several 'movements': lovely settings of poems by various authors, concerning moonlight, evening, fears about night and so on. The six poems are prefaced by a haunting prologue for natural horn and suffixed by an equally haunting epilogue.

Looking at the shellac disc on the left, however, can you see any evidence of this piece being comprised of six separate poems? No: the grooves obviously reflect light differently at different places, reflecting where the music gets louder and softer... but there's no actual, physical compartmentalisation of the music at all.

Meaning that in 1944, if you wanted to hear the Serenade, you had to hear it as a continuous stream of music, not as separate poems.

Naturally, there are pauses between the poems: the players need to get themselves into gear for what's coming and both the conductor and tenor could probably do with a bit of a breather... but, a few seconds of pause doesn't really count as a 'break' in my view.

Of course, being a 78rpm disk, you could only fit about 4 minutes of music on each side of the record in any case -so, in fact, the 'big breaks' really kick in, not by physical separation of tracks on a side of disk, but by you having to get up and turn over the disk to allow play to continue. There are six sides of shellac record for this work, which represents one side per poem. So in that sense, I guess you could say that the recorded music listening experience was broken up into separate 'bits', each bit representing one poem setting. But even though I acknowledge that, you'll note that the prologue and epilogue do not get separate sides or separate 'tracks'.

What about the LPs that came after the 78s? Surely, they split things up into tracks? In my mind, I felt sure they did... but I was again wrong!

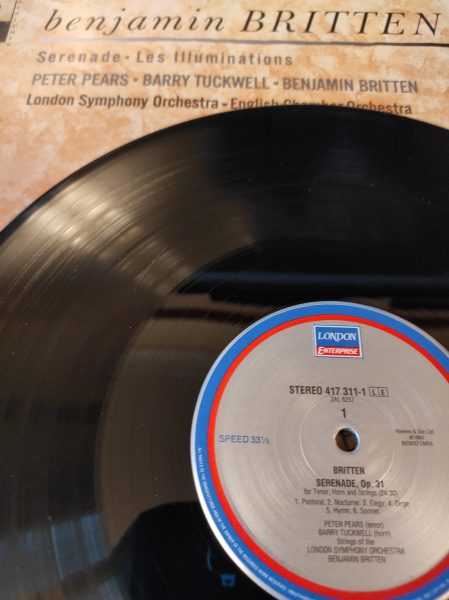

Over on the right now, you see my pristine (but rather dusty!) LP of the same Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings piece, though a copyright notice on the sleeve tells me that it dates from at least 1986.

Over on the right now, you see my pristine (but rather dusty!) LP of the same Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings piece, though a copyright notice on the sleeve tells me that it dates from at least 1986.

Do you notice six separate tracks on this disk?

No. Because there simply aren't any. It perhaps looks like that there are separated tracks because again the light is reflected at different points differently, depending on the changing loudness, orchestral density and so on. But I can promise you... there are no separated tracks... despite, you'll notice, the central label clearly that there are six 'movements', starting with '1. Pastoral' and ending at '6. Sonnet' (or, at least, it would be clear if I was better at taking photographs!)

So as late as 1986, if you wanted to listen to Britten's masterpiece, you really did now have to start at the beginning and keep going until the end -for now, everything fits on one side of an LP and you don't even get the breaks that came about by having to turn the disk over any more!

So now we move into the really digital, CD era -roughly around the mid-1980s or early 1990s. What happened when I re-bought the recording then?

Well, this:

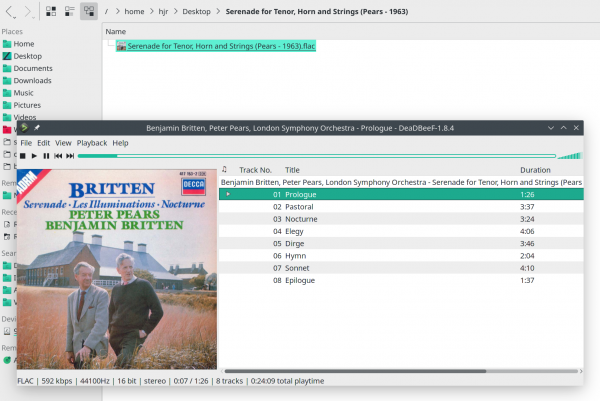

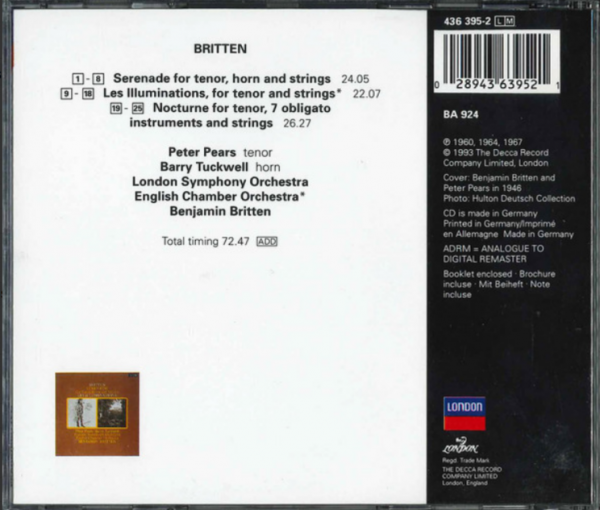

You'll notice the date over on the blurry right: no earlier than 1993. And the Serenade has suddenly morphed into a piece of eight separate tracks! Not even six, one per poem! No, on this release, even the horn prologue and epilogue are treated to their own index mark.

Why on Earth did someone in the early 1990s ever think that what was written as a single work, and was sold as a single work for nigh-on 45 years, should suddenly be shipped in 8 separate 'pieces'?! My mind boggles at the abruptness of it all, really.

Now, naturally, it being a CD, the playback from one track to another will be seamless and therefore the overall effect is of the work still being supplied as a single, organic whole. But the mere existence of track points (or index marks... call them what you will) means that it's now possible to play just the Sonnet, or to keep repeat-playing the Hymn (for example), for the first time ever. By merely providing the technology to break the work into pieces, the CD manufacturers have encouraged us to think of music as coming in little pieces, rather than large, whole compositions -because you could now do something that even as recently as 1986, you couldn't do. (Dropping a stylus at random points onto the playing surface in the hope you hit the right spot doesn't count as an equivalent experience, by the way!)

Fundamentally, then, I asked the question in that forum thread: when did it become acceptable to supply a 3-Symphony CD with 12 tracks rather than 3 (i.e., one per symphonic movement, rather than 1 per symphony)?

There's no real answer, of course -and, as correspondents in that thread point out, index marks can be quite useful ...for skipping boring bits, repeating the good bits... and a whole host of other reasons which (to my mind) simply fly in the face of how we used to listen to music and how we're really supposed to listen to music (classical music, at least).

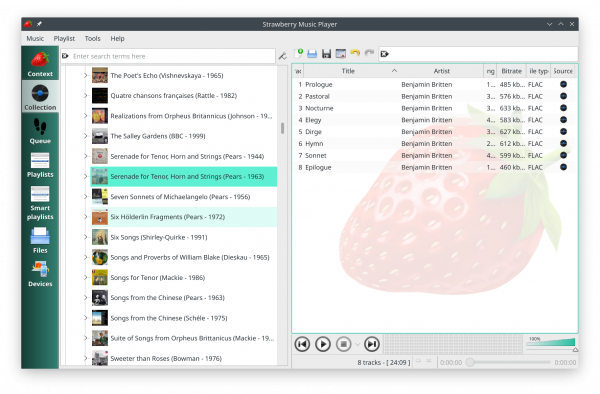

The problems in my view are magnified when you rip CDs to digital audio files. For starters, you've potentially got dozens of files (for a large oratorio, say), when "ideally" you'd really only have 3 or 4 (one per 'part' or 'Act'). Multiply by lots of CDs, and you end up managing a collection of (in my case) 65,000 "tracks" rather than around 10,000 "compositions". Every media player generally available, too, will present your music to you like this:

..as fragments of something, each with as much right to be heard as the other... and with play and pause buttons so you can stop-and-start your way through a piece that (presumably) the composer intended you to hear from beginning to end without major interruption (and which is precisely how you'd hear it if you attended a concert, for example).

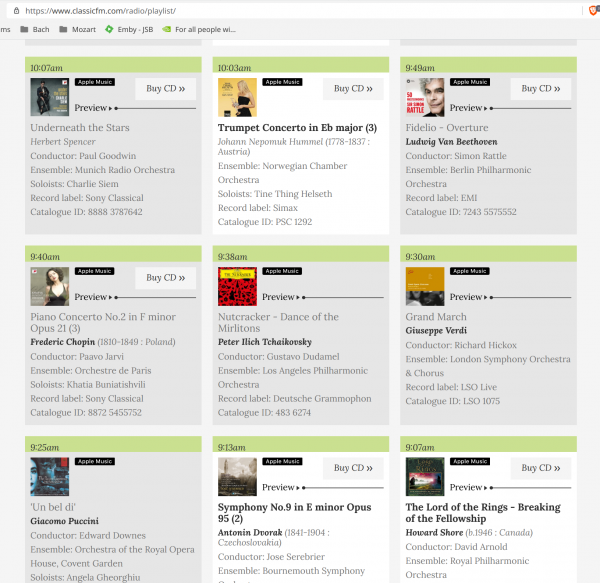

Incidentally, I also deplore an equivalent tendency for otherwise-respectable radio stations to play merely 'bits' of something, rather than the whole. Take this random grab of Classic.fm's current playlist:

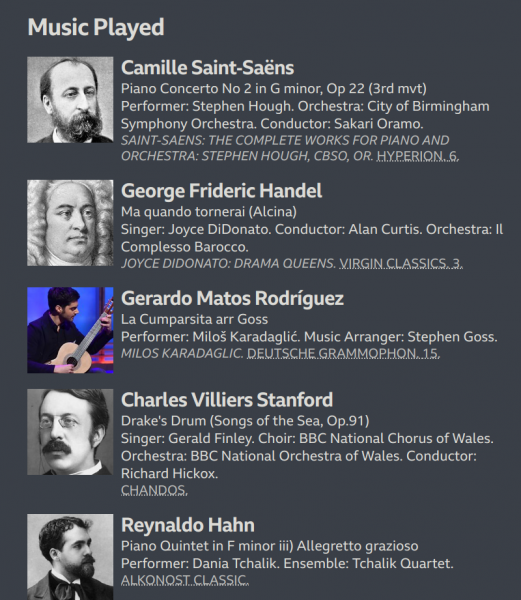

One track from one of the longest film scores ever written; the second movement only of a Dvorak symphony (the one with the good tune!); one aria from Madama Butterfly; a march from Aida; one dance from a ballet; the third movement of a piano concerto; an overture to Beethoven's only opera; the third movement of a trumpet concerto and one track from a 13-track 'medley' compilation CD. There's not a single, serious piece of music played in its entirety there. And 'posh' and 'proper' Radio 3 is often no better, at least in their morning programming:

You now get bits and pieces, never whole, complex works. It's as if everyone has decided that whole works are too taxing, too boring, too much like hard work... and yet we expect listeners to somehow switch into 'complex mode' at the drop of a hat any time they venture into the concert hall?! I blame the CD tracks for encouraging this trend!

It was to take a stand against this sort of thing that I made the deliberate design decision to make my own AMP Player (a) have no pause/play control and (b) play entire folders of music, not tracks. As per my Axioms of Classical Tagging, specifically Axiom 17, a folder of music is equivalent to a composition, so by only playing complete folders, AMP plays complete compositions. If you interrupt it, it quits. You can't pick up from where you left off later on, either: you can start over from the beginning until you get to the end, or play something new entirely. But, with AMP, you don't get to pick and choose only the good stuff: you have to learn to listen to classical music properly! Do it right in the privacy of your own home, after all, and you'll find it no great shakes to have to do it at the public concert hall.

Of course, we can't all eat everything on our plates all the time 🙂 Sometimes the Brussels sprouts are unappetising and we just fancy tucking in to the chocolate pudding instead. So, whilst AMP is a bit of a purist about how you should listen, there's absolutely nothing stopping you from having access to your music via more conventional audio players, too. It's not like I really have to go without, therefore: I have options. But, my default mode of listening now is what AMP makes it: complete compositions, without pause.

The fundamental point to make, I guess, is that whilst I'm definitely a fan of CDs, in the sense that I want to own my music, not rent it, I am not such a fan of the particular way CDs implemented digital classical music. I wish there were fewer tracks. I wish things would be composition-based primarily, with the option to go to specific tracks if really needed. And whilst AMP works well for me in that regard, that niggling problem of having to manage 60,000 tracks rather than 10,000 compositions still grates.

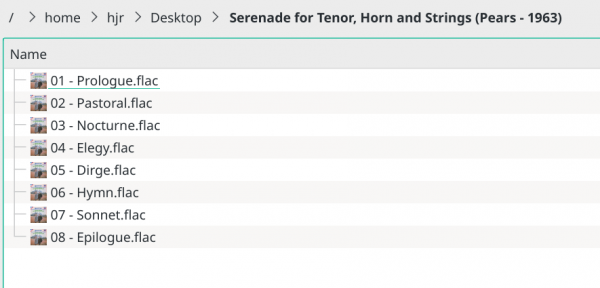

So: I've come up with a solution! The Absolutely Baching Composition-at-Once script, or CAO for short. Here's what it does. We start with a folder full of per-track nonsense ripped off a CD:

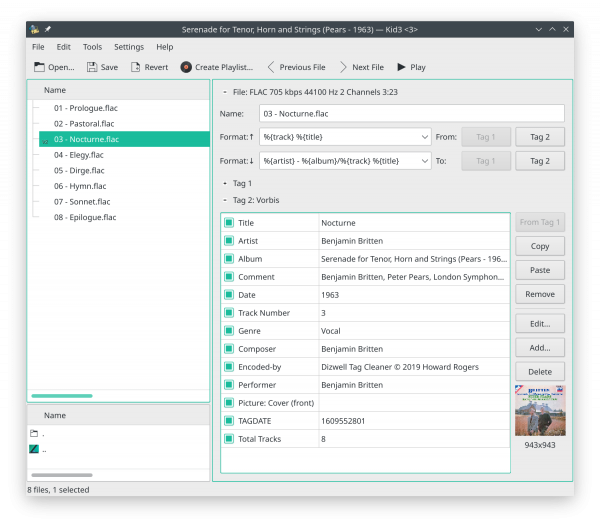

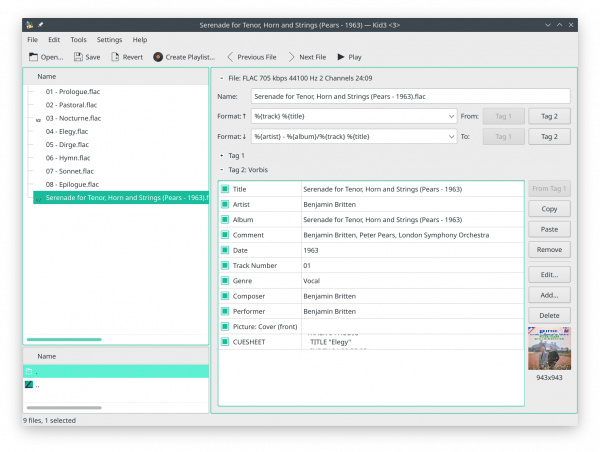

You can see that I have tagged them carefully, so they've all got album art (hence the tiny thumbnail display next to the file names) and they've all got proper track numbers. If I opened one of these files in a GUI tag editor, you'd see that all the appropriate metadata is there:

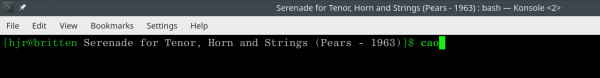

So, performers, comments, album titles, the lot. So now, in the directory those files are stored in, I run my new CAO script, as follows:

And this then happens:

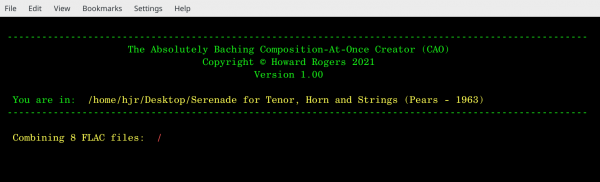

...which tells you it's combining the files into a single file. When it's done, the folder looks like this:

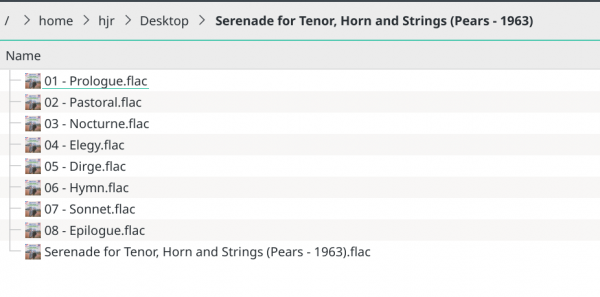

Notice there are now nine files present -and one of them has a name that tells us what's in it, but doesn't have a track number (because we don't like tracks!). Let's open that up in the same GUI tag editor as before:

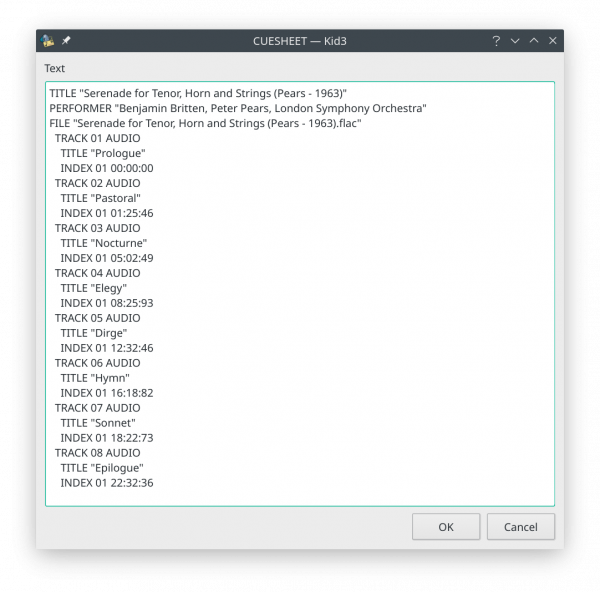

You can see I've highlighted the new file in the left panel, so the tag data being shown in the main panel belongs to the new file: and if you compare field-for-field, you should see that the new file has all the tag data the old per-track files had. There is one new additional tag present, though: CUESHEET. Click on that and click the [Edit] button and let's see what we've got there:

It's a "cue sheet", listing each constituent track, with its proper track title and with the timestemp where that particular track starts playing within the whole file. And this cuesheet is stored not on the file system (go back and check: there's only FLAC files there), but as an embedded cue sheet, as a tag within the all-in-one FLAC file itself.

CAO, in other words, is a utility that will take a folder full of separate, per-track FLAC files and concatenate them into a single big FLAC file. That 'all-in-one' file inherits all the album-wide data that the separate tracks used to be tagged with, including the original album art. To finish things off, CAO works out where all the individual tracks stopped and started and in what order and buries that information within the whole-composition file as an embedded cue sheet. Notice, though, that CAO doesn't delete the source per-track files. So at the moment, I've doubled up on my music storage for this composition. But, if I'm happy with the whole-composition file, it's just a quick manual delete of the source files using the file manager and... voilà! You've now only got trackless, whole-composition music files.

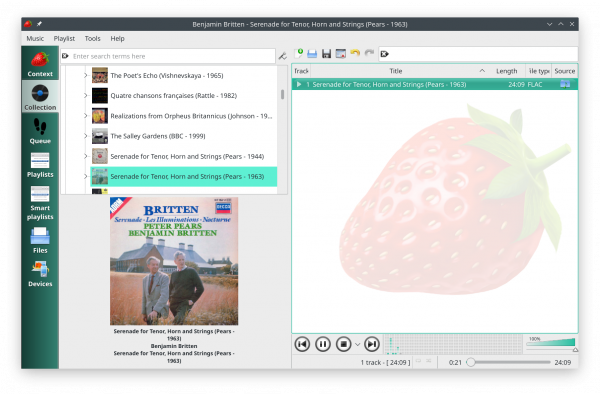

Many players (including AMP!) will happily play that one FLAC, but will also only display it as one file. For example:

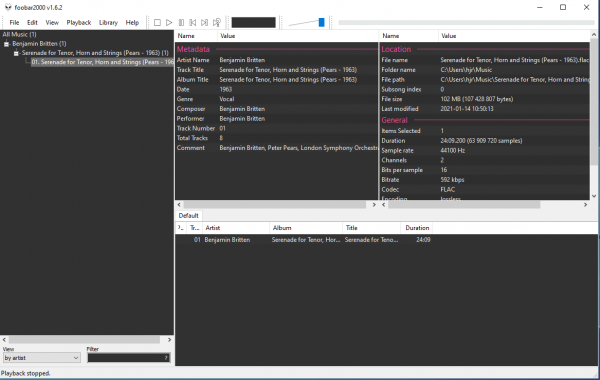

Strawberry (like its cousin Clementine) will see the new file as one, giant 24-minute long composition (which, actually, it is, of course!). In Windows, too, Foobar2000 will see none of the detail making up the file:

Again, the whole-composition appears as a single 24-minute long file... though I think that's a good thing, not a drawback, of course!

But if you change your media player, look what can happen! Here's DeadBeef on Linux:

You can see it's the same file as before: it's highlighted in the background (and you'll notice I've cleared out the per-track files). But look what DeadBeef is displaying: the tracks! DeadBeef, in other words, is reading the embedded cue sheet and displaying the tracks as they are listed within it, rather than seeing the whole-album file as just one entity. Of course, this means you can now play individual tracks in whatever order you fancy, just as before (much to my disgust, of course! :-)) ...but, you've only got one file to manage, rather than eight.

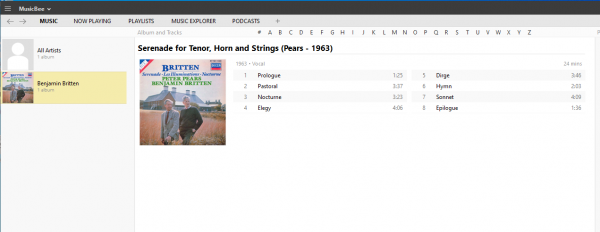

On Windows, too, Foobar2000 might not be able to read embedded cue files, but other players can. Here's my favourite, MusicBee:

Once again, a single file has been opened... but 8 tracks are displayed, because MusicBee knows how to read embedded cue files.

And just in case you try CAO out and don't like the single-file-FLAC approach, you can also run CAO in "asunder" mode: run the command cao --asunder in a folder that contains a single FLAC with an embedded cue sheet and the merge process will be reversed: you'll end up with a set of per-track FLACs, just as you started with.

In short, CAO is reversible: you can try it out, see how you go, and get your individual tracks back if at any time you don't like what a no-track existence feels like! So what's to lose?!

So, let me sum up what's been a long post.

I like owning music, and I like the click-free, scratchless perfection that digital music provides. So thumbs up for CDs! But when they were introduced, they encouraged a frivolous approach to listening to classical music, because they provided index points within compositions. I think that's a bad thing, so I've written a music player that ignores tracks and just plays entire folders (i.e., entire compositions), from beginning to end, without possibility of pausing. But now I've gone one step further: abolishing the individual tracks as physical entities entirely, by running my new CAO (Composition-at-Once) utility against them. Your music is turned into a single, giant file that contains all the data and metadata that was present in the original files, and has an embedded cue sheet so that, if you really insist, and you use an appropriate media player, you can still access individual tracks whilst physically having only one file to manage and look after. CAO, however, doesn't destroy your per-track files: that's left to you to do manually, once you've satisfied yourself that the whole-composition file is an acceptable alternative.

CAO only works on FLACs and they need to have been tagged up properly (and thus have proper track numbers and so on) before CAO can do anything meaningfully with them (without track numbers, for example, it has no way of knowing what order to pack the tracks into the whole-composition file, which could get interesting!). If you've ripped a CD via my own CDDR program and then polished off its track titles and numbers in CCDT, for example, then you'll be in good shape to run CAO against the resulting files to turn them back into a whole-composition single file.

CAO is available as a simple Bash script which you download to $HOME/Downloads and then install by issuing the following commands:

sudo chmod +x $HOME/Downloads/cao.sh sudo mv $HOME/Downloads/cao.sh /usr/bin/cao.sh sudo ln -s /usr/bin/cao.sh /usr/bin/cao

Those commands make the download executable as a program; moves it to a system folder that should be in your path (and thus can be run from anywhere within the file system); and finally creates a symbolic link that allows you to run the program by typing plain 'cao' rather than having to remember to type the '.sh' extension.

I'll write up some proper documentation for the program before too long, but otherwise: just type 'cao' in a folder full of FLACs and see what happens: the program is not very interactive and doesn't prompt you for a bazillion things before getting on and doing what it was designed to do! Remember to check the metadata associated with the still-surviving per-track files and compare it to the metadata created for the whole-composition file. If you're happy, delete the per-track files!

Obviously, I would strongly suggest that you copy small bits of your music collection to a temporary working directory and test CAO on the copy before committing yourself to applying its work to your actual, live music collection! Though CAO is not destructive itself and requires you to delete the per-track files, it's still not something you want to do without a lot of careful thought and testing!

But if you are as fed up with the casual attitude to classical music listening that I think the introduction of lots of CD 'tracks' has caused as I am, I commend CAO to you!